I am excited to say this essay was accepted by Kepler College to be displayed on their website. To read the article there please follow this link.

———————————————————————————————————————————

Born Mary Godwin, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley was the daughter of the revolutionary feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft, whose powerful treatise, Vindication of the Rights of Woman, opened up new avenues of possibility for the education of women at the commencement of the 19th century. Her daughter was one such beneficiary of Wollstonecraft’s desire to reform women’s education, going on to publish the wildly popular novel Frankenstein at the young age of 20. A look at the planetary aspects of Mary Shelley’s natal chart, using the perspective of archetypal astrology, can help illustrate how the archetypal energies correlated with the planets of our solar system were expressed in her personal life and in her writing, with a particular focus on her masterwork, Frankenstein. An analysis of the world transits, and the personal transits they form to Shelley’s natal chart, at the time of the publication of Frankenstein provide further insight into Shelley’s writing.

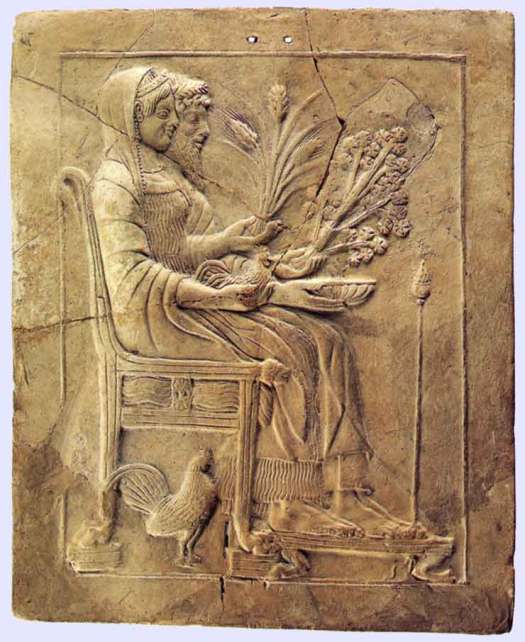

Mary Godwin, who became Mary Shelley upon her marriage to the Romantic poet Percy Shelley, was born August 30, 1797 at 11:20 pm in London, England. Most prominent in her chart is a triple conjunction of the Sun, Mars, and Uranus in the sign of Virgo, in a tight 180° opposition to Pluto, with Mars closest to Pluto in the opposition. The Sun is archetypally correlated with the principle of the self, of one’s central identity and focus, and the areas in which one shines or expresses oneself most prominently. Uranus, the first of the outer planets to be discovered in the modern era, is correlated with the revolutionary impulse, with breakthrough, rebellion, genius, brilliance, technology, electricity, the young, and the new. Sun-Uranus aspects are often found in the natal charts of brilliant individuals whose work has provided some kind of breakthrough or revolutionary shift in consciousness or worldview, from Copernicus, Galileo, and Kepler, to Newton, Kant, and Freud.[1] The planet Uranus is archetypally correlated with the Greek myth of Prometheus, the Titan who stole fire (a symbol for consciousness) from the Gods and gave it to humanity. Mary Shelley’s husband, Percy Shelley, was also a Sun-Uranus figure. His expression of the archetypal complex can clearly be seen in his poem Prometheus Unbound.

Mary Godwin, who became Mary Shelley upon her marriage to the Romantic poet Percy Shelley, was born August 30, 1797 at 11:20 pm in London, England. Most prominent in her chart is a triple conjunction of the Sun, Mars, and Uranus in the sign of Virgo, in a tight 180° opposition to Pluto, with Mars closest to Pluto in the opposition. The Sun is archetypally correlated with the principle of the self, of one’s central identity and focus, and the areas in which one shines or expresses oneself most prominently. Uranus, the first of the outer planets to be discovered in the modern era, is correlated with the revolutionary impulse, with breakthrough, rebellion, genius, brilliance, technology, electricity, the young, and the new. Sun-Uranus aspects are often found in the natal charts of brilliant individuals whose work has provided some kind of breakthrough or revolutionary shift in consciousness or worldview, from Copernicus, Galileo, and Kepler, to Newton, Kant, and Freud.[1] The planet Uranus is archetypally correlated with the Greek myth of Prometheus, the Titan who stole fire (a symbol for consciousness) from the Gods and gave it to humanity. Mary Shelley’s husband, Percy Shelley, was also a Sun-Uranus figure. His expression of the archetypal complex can clearly be seen in his poem Prometheus Unbound.

Mary Shelley’s personal expression of the Sun-Uranus combination comes through in the brilliance of her individual expression in her breakthrough first novel, which even has the apt subtitle The Modern Prometheus. The character of Victor Frankenstein is that of a rebel seeking to create life by means of technological innovation, all of which are Uranian themes. He desires to create new life alone, not as father and mother, but to elevate himself to the role of God the Father, the individual solar hero on his quest of technological prowess. Frankenstein takes on the role of both father and mother, rebelling against the order of nature, doing so in an act of technological breakthrough and brilliance. While working, Frankenstein speaks of those he would create, saying “No Father could claim the gratitude of his child so completely as I should deserve theirs.”[2] Yet, he must also suffer the consequences of achievement. Like Prometheus, whose gift to humanity leads to his eternal punishment—chained to a rock while an eagle consumes his liver each day only to have it grow back again each night—Frankenstein is haunted by the life he gave, the monster he created out of his own hubris and ambition.

Mary Shelley’s Sun-Mars-Uranus triple conjunction is, as mentioned above, in opposition to Pluto. The Uranus-Pluto opposition Shelley is born under is the primary transit that defined the tumultuous era of the French Revolutionary Period. The Uranus-Pluto impulse is toward revolutionary change on a mass scale, the liberation of the repressed and the oppressed, and the unleashing of the taboo. It is the same transit that defined the 1960s countercultural era and our current moment of world revolutions and protests, from the Arab Spring to the Occupy Movement, to the overturning of the Defense of Marriage Act in the United States this current summer.

An interesting connection between Mary Shelley and her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, is that Wollstonecraft was born with Uranus square Pluto in 1759 and published her masterwork, Vindication of the Rights of Woman, under the Uranus-opposite-Pluto in 1792. Her daughter was born just five years later in 1797 under the same Uranus-Pluto transit, and she went on to publish her own masterpiece, Frankenstein, under the subsequent Uranus square Pluto that was just beginning to come into the orb of influence in 1818. Both mother and daughter’s writing has a revolutionary quality: they were both breaking through the gender barrier in their era that oppressed female writers, and female expression as a whole.

The quality of Shelley’s Frankenstein also expresses Uranus-Pluto archetypal themes in the eruption of the shadow in her story which tells of the creation, through the Uranian technological spark of life, of a Plutonic monster. Shelley reveals and shines light upon (Sun-Uranus) the potential monstrosity (Pluto) of technology (Uranus), as well as the hubris of the modern age and the notion of progress, demonstrating how the sudden break (Uranus) with from the course of nature (Pluto) can unleash (Uranus) tremendous horrors (Pluto). In Frankenstein’s words he describes,

One secret which I alone possessed was the hope to which I dedicated myself; and the moon gazed on my midnight labors, while, with unrelaxed and breathless eagerness, I pursued nature to her hiding places.[3]

The relentless pursuit of nature, the reference to ‘her hiding places,’ and even the idea of a ‘secret. . . possessed’ evoke the underworld nature of the Plutonic, while the sense of the technological secret of life held by a single individual reflects the Sun-Uranus complex. Interestingly, this pursuit of nature is echoed by Dr. Frankenstein’s vengeful pursuit of the monster across the northern wilderness in the latter portion of the book.

The manner in which the horror of Shelley’s narrative unfolds clearly reflects not only her Sun-Uranus conjunction opposite Pluto, but also the Mars-Pluto opposition that is part of this larger complex in her natal chart. Mars correlates with the archetype of the warrior, with a potential range of manifestations from energy, action, and athleticism, to anger and even violence. The archetype of Pluto deepens any archetype with which it is in aspect, so the Mars-Pluto combination can potentially come through as a deep rage or potentially murderous violence, which is clearly expressed in the revenge of the monster of Shelley’s narrative. That Shelley has the Sun in aspect with her Mars-Pluto opposition can be seen in the individual embodiment of the violent shadow, both literally in the monster but also in the individual acts of Frankenstein that brought about the monster’s creation.

Briefly, I would like to touch on a few other aspects in Shelley’s chart that come through in the nature and style of her writing. Shelley has a tight Sun-Neptune sextile which is beautifully captured in a sentence she used to describe herself as a child: “As a child I scribbled. . . Still I had a dearer pleasure than this, which was the formation of castles in the air.”[4] The archetype of Neptune correlates, in one form of its expression, with the imagination and transcendence, which come through in this whimsical, imaginal quote illustrating Shelley’s innate ability to create imaginative narrative. She is also born with a Mercury-Venus conjunction, which can be seen in the beautiful, lyrical quality of her writing. The archetype of Mercury correlates with all forms of communication and expression—from writing, to thinking, speaking, and sensing—while the archetype of Venus correlates to beauty and artistry. Shelley’s Mercury-Venus can also be seen in the romantic fairy-story qualities of some of her other works, such as The Dream or The Heir of Mandolfo. Furthermore, Mercury is in a tight sextile to the Moon in Shelley’s chart, an example of which is the narrative form in which Frankenstein is written: a series of letters. Letter-writing is often intimate and familiar, and in this case also familial, all of which are Lunar qualities, in this instance expressed in Mercurial written form.

While much more could be elaborated in Mary Shelley’s natal chart, I would like to turn to the world transits that were in the sky at the time Frankenstein was published, on January 1, 1818. On that day, and for a short time before and after the publication date, there was a stellium in Sagittarius of Venus, Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune, with the smaller orbit of Venus bringing it briefly into the longer conjunction of Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune, and the even longer conjunction of Uranus-Neptune that defined much of the Romantic era. While there are many complex ways in which this quadruple conjunction manifested in world events, the particular expression in relation to the publication of Frankenstein can be seen in the successful release of a beautiful piece of literary art produced by the creative imagination. The archetype of Jupiter grants success to whatever it touches, while Venus relates to the artistic expression, and Neptune to the imagination behind the project. Jupiter-Uranus alignments in world history regularly correlate to successful breakthroughs and the inauguration of new initiatives, and have been found to correlate with the first successful publications of numerous authors, including of course Mary Shelley.[5]

While much more could be elaborated in Mary Shelley’s natal chart, I would like to turn to the world transits that were in the sky at the time Frankenstein was published, on January 1, 1818. On that day, and for a short time before and after the publication date, there was a stellium in Sagittarius of Venus, Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune, with the smaller orbit of Venus bringing it briefly into the longer conjunction of Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune, and the even longer conjunction of Uranus-Neptune that defined much of the Romantic era. While there are many complex ways in which this quadruple conjunction manifested in world events, the particular expression in relation to the publication of Frankenstein can be seen in the successful release of a beautiful piece of literary art produced by the creative imagination. The archetype of Jupiter grants success to whatever it touches, while Venus relates to the artistic expression, and Neptune to the imagination behind the project. Jupiter-Uranus alignments in world history regularly correlate to successful breakthroughs and the inauguration of new initiatives, and have been found to correlate with the first successful publications of numerous authors, including of course Mary Shelley.[5]

In her personal transits, the Venus-Jupiter-Uranus-Neptune stellium was conjoining Shelley’s natal Moon. While the archetype of the Moon is present in all individuals and certainly cannot be simply correlated with all women or “the feminine,” at the time Shelley lived women were often relegated or confined solely to the Lunar realms of home, family, and domestic matrimony by the then dominant patriarchal structures (which had largely appropriated the Solar archetypal role of the individual shining hero as a symbol of “the masculine”). The significance of the Venus-Jupiter-Uranus-Neptune stellium conjoining Shelley’s Moon can be seen in that she would have, in her time, been viewed, because she was a woman, as a Lunar figure who was successfully breaking out of the constrictive mold that did not encourage creative artistic or literary expression by women. The significance of the Moon in this particular case is not because she is a woman, but because of the primarily Lunar role women were usually required to take on. The archetypal energy of the successful Lunar figure is doubled by a transit that would have lasted for only a few hours on the particular day of publication: the Moon in the sky was transiting in opposition to Shelley’s natal Jupiter, which may have provided an increased sense of emotional joy and success for her.

Another significant world transit that was just beginning to come into orb at the time of publication, but which would have become more exact as the book was disseminated and read by the public, was the Saturn-Pluto conjunction of 1818. The energy of this transit would have been intensified for Shelley because, at the time of publication, Saturn was conjoining her natal Pluto as well. The archetype of Saturn is the reality principle that correlates to mortality, death, and gravity, but also to maturity and wisdom; Saturn is archetypally both hard consequences and the learning acquired from consequences. Saturn-Pluto correlates to the shadow side of the encapsulated egoic will to power that is so clearly expressed in Frankenstein. In his book on archetypal astrology, Cosmos and Psyche, Richard Tarnas describes Frankenstein as Shelley’s “prophetic Gothic masterpiece that depicted the monstrous shadow of the technological will to power.”[6] Shelley’s tale is one of death (Saturn) and destruction (Pluto), of moral (Saturn) depravity (Pluto), and of the Saturnian consequences of the soaring heights of Dr. Frankenstein’s, and modernity’s, Sun-Uranus visions of progress.

Interestingly, the day Frankenstein was published the Sun in the sky was transiting opposite Shelley’s natal Saturn, shining a light on the principle of death, as well as the profound consequences of individual actions. Frankenstein is also a shining (Sun) example of a piece of narrative art that has withstood the test of time (Saturn) and come down to us today as a revered piece of literature: another expression of the Sun-Saturn archetypal complex that brought this book into the world from the pen of Mary Shelley.

To read the complete works of Mary Shelley the kindle edition very inexpensive and available here.

Works Cited

Shelley, Mary. The Original Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus. Edited by Charles

E Robinson. New York, NY: Vintage Classics, 2008.

Tarnas, Richard. Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View. New York, NY: Viking Penguin, 2006.

Tarnas, Richard. Prometheus the Awakener: An Essay on the Archetypal Meaning of the

Planet Uranus. Woodstock, CT: Spring Publications, 1995.

Teacher, Janet Bukovinsky. Women of Words: A Personal Introduction to Thirty-Five

Important Writers. Philadelphia, PA: Courage Books, 1994.

[1] Richard Tarnas, Prometheus the Awakener: An Essay on the Archetypal Meaning of the Planet Uranus, (Woodstock, CT: Spring Publications, 1995).

[2]Mary Shelley, The Original Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus, ed. Charles E Robinson (New York, NY: Vintage Classics, 2008).

[3] Shelley, Frankenstein.

[4] Shelley, qtd. in Janet Bukovinsky Teacher, Women of Words: A Personal Introduction to Thirty-Five Important Writers (Philadelphia, PA: Courage Books, 1994), 17.

[5] Richard Tarnas, Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View, (New York, NY: Viking Penguin, 2006).

[6] Richard Tarnas, Cosmos and Psyche, 268.