The essay “The Red Book and the Red Book: Jung, Tolkien, and the Convergence of Images,” which emerged out of this presentation, is available here.

The essay “The Red Book and the Red Book: Jung, Tolkien, and the Convergence of Images,” which emerged out of this presentation, is available here.

To give birth to the ancient in a new time is creation. . . .

The task is to give birth to the old in a new time.”

– C.G. Jung[1]

“Fantasy remains a human right: we make in our measure and in our derivative mode, because we are made: and not only made, but made in the image and likeness of a Maker.”

– J.R.R. Tolkien[2]

This essay was the seed of what is currently being developed into my Ph.D. dissertation, which will be available in spring 2017. Many of the ideas have been expanded and revised as I have brought in new perspectives and further research.

When you close your eyes and images arise spontaneously, what is it that you are seeing? The inside of your mind? Your imagination? The interior of your soul? Are you seeing something others can see also? Is it real? Is it inside just you, or inside everyone? Is it only internal, or could it be external as well? Might you actually be seeing a place, a realm, into which not only you but others also can enter? Does this realm have a name? These are questions I have often asked myself, when I close my eyes and am beckoned down some new road I have never encountered in this green world beneath the Sun, or when I read a story flowing from the pen of some author and find that I somehow already know the tale, am familiar with the names, have seen the images of these places before. Reading stories is an anamnesis, a discovery of the new found by treading down the paths of the old. Creativity, creation from the imagination, is that rediscovery, that recollection and remembrance. As C.G. Jung writes, “To give birth to the ancient in a new time is creation. . . . The task is to give birth to the old in a new time.” But how do we begin to undertake that task? And what does it look like when we do?

The Red Book. Carl Gustav Jung undertook the task of giving birth to the ancient in his time by following the meandering pathways of his imagination into the darkest depths of his psyche; the images with which he returned he inscribed in black and red letters, accompanied by rich illustrations, on large pages bound by two covers of red leather.

The Red Book of Westmarch. J.R.R. Tolkien set out to write a mythology—“a body of more or less connected legend,”[3] cosmogonic myths and romantic tales whose “cycles should be linked to a majestic whole”[4]—which came to the world in the form of The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion. But within the world of the story itself these tales are written out in a book that has been passed on from generation to generation: inscribed in black and red letters, accompanied by rich illustrations, in a large book bound by two covers of red leather. The book is referred to—by Tolkien who presents himself simply as the translator of this work—as The Red Book of Westmarch.

At first glance the parallel names of Jung’s and Tolkien’s respective Red Books just seem to be an odd coincidence. They could not actually have anything to do with one another, or share anything in common in content. On the one hand, Jung was one of the founders of depth psychology, an explorer of the unconscious, of the archetypal realm, of the phenomenon of synchronicity, a man of Switzerland born in 1875. On the other hand, Tolkien was firmly English, a philologist, famous author of The Lord of the Rings, one of the founders of the genre of fantasy literature, a younger man born in 1892. At first glance there seems to be little common ground between the two men, let alone between their work. There have, of course, been Jungian analyses of Tolkien’s work—focusing on both the content of his fiction, and on aspects of his biography. But, as of yet, there have been few, if any, extensive “Tolkienian analyses,” [5] to use Lance Owens’ phrase, of Jung and his work, particularly his work with active imagination and its product: the Liber Novus, also named The Red Book.

As I began to explore Jung’s Red Book in the context of Tolkien’s writings I started to find certain similarities between their work beyond the titles and color of the leather binding. There seemed to be a certain resonance between the two bodies of work, a convergence of images—a synchronicity, in Jung’s terminology—a synchronicity of imagination. The following essay is not so much the laying out of one particular thesis, but rather an exploration of this synchronicity of images, a journey through art, language, and story. Because of the nature of this exploration I will also quote at greater length than I usually might, because the original words of each of these men carries great power in themselves.

The first parallel that stood out to me was the timing of when Jung began his “Red Book period”—the time of his psychological descent when the fantasy images began to come to him in waking life—and when Tolkien began making an unusual series of drawings in a sketchbook he entitled The Book of Ishness. In 1913 both men, Jung an established psychoanalyst, Tolkien a young man early in his undergraduate studies at Oxford, took an unusual turn in their lives, turning away from the outer images of the world of common day and focusing instead upon the inner images of the imagination. Jung’s Red Book period is considered to have spanned the years 1913-1930,[6] but the primary content of his visions came to him from late 1913 through around 1917, the first vision taking place on December 12, 1913.[7] The majority of the sketches in Tolkien’s Book of Ishness were done over a shorter period of time: from December 1911 through the summer of 1913 he made his “Earliest Ishnesses,”[8] but he continued to add to The Book of Ishness up until 1928.[9] Alongside the visionary drawings another form of creativity was emerging through Tolkien as well: the arts of language. Tolkien was trying his hand at writing poetry and prose not only in English, but in languages of his own invention as well. The first mythic stories that were to become part of The Silmarillion Tolkien wrote down in September 1914.[10] Although the primary creative period for both Jung and Tolkien was during these potent years of the 1910s, they each spent the next forty years of their lives developing the material they encountered during that time.[11] As Jung wrote of that period:

The years when I was pursuing my inner images were the most important in my life—in them everything essential was decided. It all began then; the later details are only supplements and clarifications of the material that burst forth from the unconscious, and at first swamped me. It was the prima materia for a lifetime’s work.[12]

One means of understanding the simultaneity of Jung’s and Tolkien’s periods of creative imagination is archetypal astrology, which interprets archetypally the relational positions of the planets in the sky at the time Tolkien and Jung were having these unusual experiences. Yet, although astrology sheds a strong light upon the timing of the outpouring of this imaginal material, that is not the primary direction this particular essay will be taking. However, I would briefly like to point out a few significant planetary alignments before moving deeper into exploring the art and writings of Jung and Tolkien.

From 1899-1918 there was an opposition between the slow-moving outer planets Uranus and Neptune.[13] The archetype of Neptune, as Richard Tarnas writes, “is considered to govern the transcendent dimensions of life, imaginative and spiritual vision, and the realm of the ideal.”[14] He goes on to say that Neptune “rules both the positive and negative meanings of enchantment—both poetic vision and wishful fantasy, mysticism and madness, higher realities and delusional unreality.”[15] Finally, “The Neptune principle has a special relation to the stream of consciousness and the oceanic depths of the unconscious, to all nonordinary states of consciousness, to the realm of dreams and visions, images and reflections.”[16] In contrast, the planet Uranus, as Tarnas also writes,

is empirically associated with the principle of change, rebellion, freedom, liberation, reform and revolution, and the unexpected breakup of structures; with sudden surprises, revelations and awakenings, lightning-like flashes of insight, the acceleration of thoughts and events; with births and new beginnings of all kinds; and with intellectual brilliance, cultural innovation, technological invention, experiment, creativity, and originality.[17]

When the archetypal natures of these two planets, Uranus and Neptune, come into geometrical relationship with each other, personal and world events with increasing frequency tend to reflect the combined energies of these archetypes. Uranus-Neptune alignments correlate with

widespread spiritual awakenings, the birth of new religious movements, cultural renaissances, the emergence of new philosophical perspectives, rebirths of idealism, sudden shifts in a culture’s cosmological and metaphysical vision, rapid collective changes in psychological understanding and interior sensibility . . . and epochal shifts in a culture’s artistic imagination.[18]

The visionary periods of both Jung and Tolkien perfectly exemplify the characteristic manifestations of Uranus-Neptune alignments. The most potent time of both men’s imaginal experiences took place in the sunset years of the early 20th century opposition alignment, from 1913-1917. Furthermore, they were not the only of their contemporaries to be having fantasy visions and translating them into paint and the written word.[19]

The following two axial, or quadrature, alignments of Uranus and Neptune since the turn of the 20th century have also correlated to significant periods in terms of the work of both Tolkien and Jung. During the square alignment of the 1950s Tolkien’s masterpiece The Lord of the Rings was published in three volumes in 1954 and 1955. Under the same alignment, in 1957, Jung began working with Aniela Jaffé on compiling his autobiographical memoir Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Finally, under the most recent alignment of Uranus and Neptune, the conjunction that lasted from 1985-2001,[20] the film renditions of The Lord of the Rings, directed by Peter Jackson, were produced in New Zealand, with the first installation released in December 2001. Also at the end of that same Uranus-Neptune alignment in the year 2000, the decision was made by the Society of Heirs of C.G. Jung to at last publish the long-awaited seminal work of Jung’s career, his Liber Novus, The Red Book.[21]

Intimations of the imaginal explorer Jung would become were present from his childhood, particularly in his relationship to his dreams, visions, and sense of having two personalities, one of whom he felt was connected to an earlier historical period. Jung referred to these two personalities simply as No. 1 and No. 2. No. 1 was the personality who corresponded with his age and current time in history, a schoolboy who struggled with algebra and was less than self-assured.[22] No 2. Jung felt was an old man, who perhaps lived in the 18th century,[23] but also had a mysterious connection to the Middle Ages.[24] Yet No. 2 was also not tied to history or even time, for he lived in “God’s world,” a boundless, eternal realm.[25] Jung described this realm as follows:

Besides [personality No. 1’s] world there existed another realm, like a temple in which anyone who entered was transformed and suddenly overpowered by a vision of the whole cosmos, so that he could only marvel and admire, forgetful of himself. . . . Here nothing separated man from God; indeed, it was as though the human mind looked down upon Creation simultaneously with God.[26]

In another description, Jung writes how he felt when experiencing life as personality No. 2, saying,

It was as though a breath of the great world of stars and endless space had touched me, or as if a spirit had invisibly entered the room—the spirit of one who had long been dead and yet was perpetually present in timelessness until far into the future. Denouements of this sort were wreathed with the halo of the numen.[27]

The vision Jung paints in these descriptions brings to mind a quote from Tolkien’s essay “On Fairy-Stories,” in which he describes a similar perspective, like a view from above, that one gains while in the realm of Faërie—Faërie being Tolkien’s term for the realm of imagination. He writes,

“The magic of Faërie is not an end in itself, its virtue is in its operations: among these are the satisfaction of certain primordial human desires. One of these desires is to survey the depths of space and time. Another is to hold communion with other living things.”[28]

Tolkien too had the sense he somehow had been born into the wrong time. His interests lay primarily in the Middle Ages, and he was drawn to ancient languages such as Anglo-Saxon, Gothic, Old Icelandic, and several other tongues no longer spoken in the contemporary world. Tolkien had an intuitive feel for these languages as if they were his own. He was most inspired by pre-Chaucerian literature, particularly favoring the heroic myths of the Finnish Kalevala, and the world of monsters and dragons presented in the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf. Even his voice had an other-worldly or ancient tone to it. As his biographer Humphrey Carpenter writes, “He has a strange voice, deep but without resonance, entirely English but with some quality in it that I cannot define, as if he had come from another age or civilization.”[29]

Both Jung and Tolkien painted and drew as children, but their art, leading into adulthood, was always representational in nature, usually of the surrounding landscapes.[30] However, there was an abrupt change in the style of each of their artwork from the early 1910s onward, moving from depictions of topography to abstract, semi-figurative, and symbolic art.[31] [32]

One of the earliest visions that came to both Jung and Tolkien was of major significance to each of them: an overpowering Flood, or as Tolkien sometimes called it, the Great Wave. The first of Jung’s Flood visions came to him while awake, on October 17, 1913:

In October, while I was alone on a journey, I was suddenly seized by an overpowering vision: I saw a monstrous flood covering all the northern and low-lying lands between the North Sea and the Alps. . . . I saw the mighty yellow waves, the floating rubble of civilization, and the drowned bodies of uncounted thousands. Then the whole sea turned to blood.[33]

Two weeks later Jung had the vision again, this time accompanied by a voice saying, “Look at it well; it is wholly real and it will be so. You cannot doubt it.”[34]

An uncannily similar vision came also to Tolkien, both while awake and while sleeping, beginning when he was about seven years old and continuing throughout much of his adult life.[35] He called the vision his “Atlantis-haunting”:

This legend or myth or dim memory of some ancient history has always troubled me. In sleep I had the dreadful dream of the ineluctable Wave, either coming out of the quiet sea, or coming in towering over the green inlands. It still occurs occasionally, though now exorcized by writing about it. It always ends by surrender, and I wake gasping out of deep water.[36]

When World War I broke out in August 1914 Jung recognized that his vision of the destructive Flood was prophetic of the war; his interior images were reflective of the external political and cultural situation occurring in Europe. The outbreak of the war indicated to Jung that he was not, as he had been afraid, going mad, but was rather a mirror of the madness unfolding in the external world. Tolkien, being an Englishman and of a younger generation than Jung, fought in that very war that Jung’s vision had prophesied. Needless to say, the war had a tremendous effect upon Tolkien, particularly the Battle of the Somme in which two of his most beloved friends were killed.[37] Later in his life, as Tolkien was creating The Lord of the Rings, world events began to reflect what he had already written in his narrative. As his close friend, and fellow Oxford don, C.S. Lewis wrote, “These things were not devised to reflect any particular situation in the real world. It was the other way round; real events began, horribly, to conform to the pattern he had freely invented.”[38]

The next vision that came to Jung, and the first that he wrote out in calligraphic hand in his Red Book, marked the beginning of his “confrontation with the unconscious.”[39] To get a fuller sense of the experiential nature of this vision, I will quote at length from Memories, Dreams, Reflections:

It was during Advent of the year 1913—December 12, to be exact—that I resolved upon the decisive step. I was sitting at my desk once more, thinking over my fears. Then I let myself drop. Suddenly it was as though the ground literally gave way beneath my feet, and I plunged down into dark depths. I could not fend off the feeling of panic. But then, abruptly, at not too great a depth, I landed on my feet in a soft, sticky mass. I felt great relief, although I was apparently in complete darkness. After a while my eyes grew accustomed to the gloom, which was rather like a deep twilight. Before me was the entrance to a dark cave, in which stood a dwarf with a leathery skin, as if he were mummified. I squeezed past him through the narrow entrance and waded knee deep through icy water to the other end of the cave where, on a projecting rock, I saw a glowing red crystal. I grasped the stone, lifted it, and discovered a hollow underneath. At first I could make out nothing, but then I saw that there was running water. In it a corpse floated by, a youth with blond hair and a wound in the head. He was followed by a gigantic black scarab and then by a red, newborn sun, rising up out of the depths of the water. Dazzled by the light, I wanted to replace the stone upon the opening, but then a fluid welled out. It was blood. A thick jet of it leaped up, and I felt nauseated. It seemed to me that the blood continued to spurt for an unendurably long time. At last it ceased, and the vision came to an end.[40]

In this inaugural vision of The Red Book are contained many symbolic images. But for this particular study, what stands out to me are the numerous parallels to images in Tolkien’s own works of the many underworld, underground journeys that take place in Middle-Earth: the dark journey through the lost Dwarf realm of Moria in which Gandalf is lost in a battle with Shadow and Flame; Frodo and Sam’s fearful passage through the monstrous spider Shelob’s midnight tunnel on the borders of Mordor, which has resemblance to the giant scarab Jung describes; Aragorn and the Grey Company’s journey through the Paths of the Dead, in which they encounter a dead host of restless shades, another parallel to Jung’s encounter with the Dead deeper into The Red Book; Bilbo’s encounter with the dragon Smaug in the dark halls of Erebor, the Lonely Mountain; and Bilbo’s fateful encounter with the twisted creature Gollum, whose lair was deep within a mountain cavern, upon a little island rock set within the icy waters of a subterranean lake. Upon that rock, like the red crystal of Jung’s vision, lay long-hid the One Ring, the Ring of Power made by the Dark Lord Sauron. In both stories the heart of the narrative begins here, upon this island rock, where a lost treasure of unknown power is hid, awaiting for a new hand to grasp it.

At about the same time Jung was experiencing these early fantasies, Tolkien started to draw the visionary illustrations in his Book of Ishness. Two particularly stand out in correlation to Jung’s own vision, as they seem to symbolize a similar entrance into an underworld imaginal realm. The first is titled simply Before, and depicts a dark corridor lit with flaming torches, leading to a gaping doorway from which a red glow issues ominously (see Figure 1).

Lance Owens describes Before as “primitive, quick, a statement of the deep dream world.”[41] Verlyn Flieger also comments on the sketch, saying that “The title Before conveys the dual notions of ‘standing in front of’ and ‘awaiting,’ or ‘anticipating.’ The sketch is remarkable for its mood, which conveys both foreboding (the dark corridor) and hope (the lighted doorway).”[42]

The second sketch seems to be intended to follow directly after Before: it depicts a solitary figure walking out of a doorway of the same shape as in the previous drawing, and heading down a long hall lit with many torches. The drawing is titled Afterwards (see Figure 2). The coloring is in great contrast to the stark red and black of Before; Afterwards is sketched in yellows and blues, although it too conveys a sense of darkness and gloom, yet less foreboding than the previous drawing.

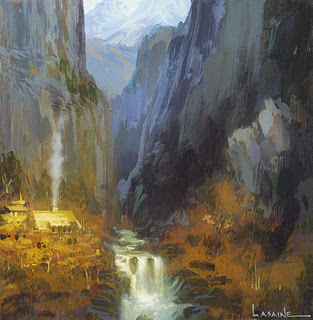

The Book of Ishness contained a series of Tolkien’s drawings, all of them symbolic or abstract in nature.[43] As previously mentioned, Tolkien underwent a shift in the subjects he chose to illustrate. As Owens explains it, Tolkien felt “a need to draw not what he saw on the outside, but what he saw on the inside.”[44] Interestingly, in 1911 not long before he began to draw his “Earliest Ishnesses,” Tolkien visited Switzerland, Jung’s homeland, for the only time in his life. He went on a walking tour through the Alps, whose majestic peaks had a tremendous impact on him.[45] How close geographically Jung and Tolkien might have been to each other at that time, one can only guess. While in Switzerland Tolkien came across a postcard on which was a painting by J. Madlener, titled Der Berggeist, “the mountain spirit” (see Figure 3). The painting depicts an old man in a cloak and wide-brimmed hat, seated beneath a tree in an alpine setting.

Many years later Tolkien made a note on this painting: “Origin of Gandalf.”[46] Within The Book of Ishness Tolkien also composed a painting he entitled Eeriness, that seems to depict a wizard-like figure bearing a staff who is walking down a long road lined with dark trees (see Figure 4). Like all the illustrations in The Book of Ishness, there is no explanation of the content of the pictures beyond their titles—we can only guess what inner images of Tolkien’s they are reflecting.

Perhaps the most striking of all the Ishnesses is the one titled End of the World (see Figure 5). In this drawing a small figure is stepping off of a cliff extending over the sea. The Sun is shining brightly down onto the scene, and seemingly within the water itself shine white stars, and a crescent Moon bends across the horizon line. Although the image of a man stepping off a cliff, and its corresponding title, may seem to be somber, even depressing, they convey a dual meaning: this is not only the “end of the world” in reference to its demise, or to the death of the individual, but it is the “end of the world” in that the individual has reached its edge and wishes to continue on his journey. As Owens says of this image, “that fellow has stepped, and he is not falling, he is walking into a Sun, into a Moon, into Stars.”[47] One might see End of the World as a symbol of the threshold Tolkien appears to have crossed at this time—the doorway to the imaginal, into what he called the realm of Faërie.

Much of Jung’s fantasy material came to him not only as images but in the form of runes and words that he would hear. No easy translation of his fantasies was available to him. As written in the Translators’ Note to The Red Book, “The task before him was to find a language rather than use one ready at hand.”[48]

When Tolkien began to take up the creation of his own language systems, it was because he too was hearing words, languages with no correlate in the outside world.[49] Owens compares Tolkien’s hearing of languages to Mozart’s experiences of hearing full melodies playing out in his mind.[50] He wished to compose languages as others composed symphonies.[51] Accompanying these languages were races of people, Elves he soon discovered, who came replete with names and histories of their own. The images of story seemed to arise from the music of the languages themselves. In a passage in The Fellowship of the Ring, Tolkien illustrates an experience Frodo has in the Hall of Fire in Rivendell while listening to Elvish music, which I believe may be a description of Tolkien’s own experience with the story visions that would accompany the Elven languages:

At first the beauty of the melodies and of the interwoven words in elven-tongues, even though he understood them little, held him in a spell, as soon as he began to attend to them. Almost it seemed that the words took shape, and visions of far lands and bright things that he had never yet imagined opened out before him; and the firelit hall became like a golden mist above seas of foam that sighed upon the margins of the world. Then the enchantment became more and more dreamlike, until he felt that an endless river of swelling gold and silver was flowing over him, too multitudinous for its pattern to be comprehended; it became part of the throbbing air about him, and it drenched and drowned him. Swiftly he sank under its shining weight into a deep realm of sleep.[52]

The same year Jung’s Red Book visions began, Tolkien came across a pair of lines in an Anglo-Saxon poem titled Crist, written by the poet Cynewulf.

Eala Earendel engla beorhtast

ofer middangeard monnum sended.

“Hail Earendel, brightest of angels

above the middle-earth sent unto men”[53]

Many years later Tolkien wrote of his finding both the names Earendel and Middle-Earth: “I felt a curious thrill . . . as if something had stirred in me, half wakened from sleep. There was something very remote and strange and beautiful behind those words, if I could grasp it, far beyond ancient English.”[54] Tolkien felt as though he had come across something he somehow already knew, a stirring of remembrance, of anamnesis. In September 1914, just after World War I broke out and while Jung was gripped by the visions of his psychological descent, Tolkien wrote his first poem about this figure Earendel, who was to become a central character in his mythology, with the slightly altered name Eärendil.

“The Voyage of Earendel the Evening Star”

Earendel sprang up from the Ocean’s cup

In the gloom of the mid-world’s rim;

From the door of Night as a ray of light

Leapt over the twilight brim,

And launching his bark like a silver spark

From the golden-fading sand

Down the sunlit breath of Day’s fiery death

He sped from Westerland.[55]

The poem is describing the journey of a lone wanderer across the night sky, a single light entering the realm of darkness before making his descent into the West, the direction in which, according to Tolkien, dwelt the Faërie realm.

The journey of the Evening Star seems to have entered Jung’s imagination also, although by another name. Upon the cornerstone of the tower he built at Bollingen, Jung had inscribed this line, among several others: “This is Telesphoros, who roams through the dark regions of this cosmos and glows like a star out of the depths. He points the way to the gates of the sun and to the land of dreams.”[56]

When Tolkien showed “The Voyage of Earendel the Evening Star” to his close friend G.B. Smith, he asked Tolkien what the poem was really about. Tolkien gave an unusual response: “I don’t know. I’ll try to find out”[57] He always maintained that the stories he was writing were true in a sense, that he was not making them up but rather discovering them. As his biographer writes, “He did feel, or hope, that his stories were in some sense an embodiment of a profound truth.”[58] Jung too, “maintained a ‘fidelity to the event,’ and what he was writing was not to be mistaken for a fiction.”[59] What then was it that both men were encountering, that appeared to be an internal experience, and yet had such a profound air of reality?

The Liber Novus, Jung’s Red Book, “depicts the rebirth of God in the soul.”[60] The Red Book is “Jung’s descent into Hell” and is “an attempt to shape an individual cosmology.”[61] Tolkien’s own Red Book, in the form of his mythology and The Lord of the Rings, is also an attempt to shape an individual cosmology and cosmogony, a world containing the God he loved and worshipped. And Tolkien also depicted a descent into Hell—into Mordor, and into worse Hells: the dark realm of Thangorodrim, the darkness of lost and corrupted souls.

Both Jung and Tolkien were drawn to the style of medieval manuscripts, with their calligraphy and illuminated letters, and emulated the medieval aesthetic in their artwork. Jung spoke of the style of language in which he wrote The Red Book, saying: “First I formulated the things as I had observed them, usually in ‘high flown language,’ for that corresponds to the style of the archetypes. Archetypes speak the language of high rhetoric, even of bombast.”[62] The language used in Tolkien’s Silmarillion, and even in the latter chapters of The Lord of the Rings, has a similar tone, sounding mythic, almost Biblical in nature.

The term “fantasy” was of great significance for both Jung and Tolkien, and although the specific language in which they defined the term differs somewhat, there are certain significant overlaps. In A Critical Dictionary of Jungian Analysis, “Fantasy” is defined as the

Flow or aggregate of images and ideas in the unconscious Psyche, constituting its most characteristic activity. To be distinguished from thought or cognition. . . . “Active” fantasies, on the other hand, do require assistance from the ego for them to emerge into consciousness. When that occurs, we have a fusion of the conscious and unconscious areas of the psyche; an expression of the psychological unity of the person.[63]

The Jungian dictionary finds a contradiction in the further definition of Fantasy, saying that Jung seemed to have “two disparate definitions of fantasy: (a) as different and separate from external reality, and (b) as linking inner and outer worlds.”[64] Although these definitions seem contrary, perhaps when read in light of Tolkien’s definition of “Fantasy” they may not seem to be quite as at odds as first appears: “Fantasy, the making or glimpsing of Other-worlds, was the heart of the desire of Faërie.”[65] Tolkien goes on to say, “Fantasy is a natural human activity. It certainly does not destroy or even insult Reason; and it does not either blunt the appetite for, nor obscure the perception of, scientific verity.”[66] He also adds, “Fantasy is a rational not an irrational activity.”[67] According to this definition, Fantasy appears highly similar to Jung’s practice of active imagination, that links a person of the external world to the internal realm of Faërie, yet is also the very heart of that separate realm of the Imagination.

Diving further into the content of The Red Book itself, there are many significant parallels simply between the style of artwork composed by Jung and Tolkien. For one, they both painted multiple dragons, symbols of the archetypal monster to be confronted in the heart of the underworld (see Figures 6, 7, 8 and 9). Another archetypal symbol both

men painted multiple times was of a great tree, that could be seen as the World Tree or the Tree of Tales. Tolkien “regularly” drew what he called the Tree of Amalion, which particularly resembled a single tree painted in Jung’s Red Book with large ornaments situated upon each branch (See Figures 10 and 11).[68] Jung wrote in his memoir, “Trees in particular were mysterious and seemed to me direct embodiments of the incomprehensible meaning of life. For that reason the woods were the place where I felt closest to its deepest meaning and to its awe-inspiring workings.”[69] Trees were beloved, even sacred, to Tolkien: “he liked most of all to be with trees. He would like to climb them, lean against them, even talk to them.”[70] The entrance to the realm of Faërie, for Tolkien, lay not underground, as was depicted in many traditional fairy-stories, but through the woods; in the world of trees lay the transition between realities. While for Jung the archetype of the World Tree played a significant role, Tolkien’s mythology had at its heart not one World Tree but two, the Two Trees of Valinor, whose intermingling silver and gold lights illuminated the newly created world before the Sun and Moon were formed of their last fruit and flower.

One of the most prominent figures Jung encounters in The Red Book is Philemon, an old man who provides guidance and teaches magic. Many chapters could be dedicated solely to Philemon and the teachings from his wisdom, but in this study I will focus primarily on his resemblance to another old man who provides guidance and is an embodiment of magic: Gandalf the Grey, one of the Istari, a wizard, who within the course of The Lord of the Rings becomes Gandalf the White and guides the Free Peoples of Middle-Earth to victory against the Dark Lord Sauron. Gandalf not only plays a similar role as Philemon, but also his original name—his Maia name by which he was known in the Undying Lands in the West, before he was sent in human form to Middle-Earth—was Olorin. The name Olorin comes from the Elvish olor which means “dream” but, as Flieger writes, “that does not refer to (most) human ‘dreams,’ certainly not the dreams of sleep.”[71] Furthermore, olor is derived from Quenya olo-s which means “vision, phantasy.”[72]

The vision of the Great Wave stayed with both Jung and Tolkien and entered into their imaginal writings. Jung wrote out one particular fantasy of the Wave that came to him January 2, 1914 in the pages of The Red Book. Yet another synchronicity was that this recurring vision, which he seemed to share with Tolkien, occurred on the eve of Tolkien’s birthday, January 3. Yet because Jung always did his practice of active imagination late at night he very well may have beheld the Great Wave after midnight, on the date of Tolkien’s twenty-second birthday. As written in The Red Book, Jung’s fantasy unfolded as follows:

“Wave after wave approaches, and ever new droves dissolve into black air. Dark one, tell me, is this the end?”

“Look!”

The dark sea breaks heavily—a reddish glow spreads out in it—it is like blood—a sea of blood foams at my feet—the depths of the sea glow—how strange I feel—am I suspended by my feet? Is it the sea or is it the sky? Blood and fire mix themselves together in a ball—red light erupts from its smoky shroud—a new sun escapes from the bloody sea, and rolls gleamingly toward the uttermost depths—it disappears under my feet.[73]

Tolkien also wrote of the Great Wave many times, in The Silmarillion, in his two unfinished tales The Lost Road and The Notion Club Papers, and as Faramir’s dream in The Lord of the Rings. He said when he bestowed the dream upon Faramir he ceased to dream of it himself, although he found out years later his son Michael had inherited the dream in his turn.[74] One of the most powerful narrations of the Great Wave takes place in the Second Age at the Downfall of Númenor, also called the Akallabêth: “Darkness fell. The sea rose and raged in a great storm . . . the Sun, sinking blood-red into a wrack of clouds.”[75]

And the deeps rose beneath them in towering anger, and waves like unto mountains moving with great caps of writhen snow bore them up amid the wreckage of the clouds, and after many days cast them away upon the shores of Middle-earth. And all the coasts and seaward regions of the western world suffered great change and ruin in that time; for the seas invaded the lands, and shores foundered, and ancient isles were drowned, and new isles were uplifted; and hills crumbled and rivers were turned into strange courses.[76]

The name Númenor, given to the island kingdom that sank beneath the waves in divine retribution for a mortal transgression of hubris, has often been mistakenly written as “Numinor,” even by Tolkien’s close friend C.S. Lewis. Tolkien felt such a mistake came from associating the name with the Latin numen, numina that is the root of the word “numinous,” a term of particular significance to Jung. Tolkien explains that the name Númenor is actually derived from the Eldarin base NDU, meaning “below, down, descend.” This base is the root of the Quenya word nume, meaning “going down, occident,” and númen “the direction or region of the sunset.”[77] Not only does the mistaken name of the land that sank beneath the Great Wave refer to the numinous, but the actual name implies a descent, the very term used for the psychological process Jung was undergoing during his Red Book period.

The power of Fantasy comes directly into the visions of The Red Book when Jung encounters the God Izdubar, a giant somewhat resembling the Norse God Thor. In the course of their conversation Jung brings up an aspect of Western science, the disenchanted world view from which he comes. The encounter of a mythic being with the disenchanted perspective of the modern world mortally wounds the God, laming him so he cannot walk and sapping his life strength away. In an attempt to save him Jung realizes that if he can convince Izdubar he is a fantasy he may have some hope in saving him. Jung’s dialogue captures both the humor and profundity of the exchange, thus I will quote at length directly from The Red Book:

I: “My prince, Powerful One, listen: a thought came to me that might save us. I think that you are not at all real, but only a fantasy.”

Izdubar: “I am terrified by this thought. It is murderous. Do you even mean to declare me unreal—now that you have lamed me so pitifully?”

I: “Perhaps I have not made myself clear enough, and have spoken too much in the language of the Western lands. I do not mean to say that you are not real at all, of course, but only as real as a fantasy. If you could accept this, much would be gained.”

Iz: “What would be gained by this? You are a tormenting devil.”

I: “Pitiful one, I will not torment you. The hand of the doctor does not seek to torment even if it causes grief. Can you really not accept that you are a fantasy?”

Iz: “Woe betide me! In what magic do you want to entangle me? Should it help me if I take myself for a fantasy?”

I: “I know that the name one bears means a lot. You also know that one often gives the sick new names to heal them, for with a new name, they come by a new essence. Your name is your essence.”

Iz: “You are right, our priests also say this.”

I: “So you are prepared to admit that you are a fantasy?”

Iz: “If it helps—yes.”. . .

“A way has been found. You have become light, lighter than a feather. Now I can carry you.” I put my arms round him and lift him up from the ground; he is lighter than air, and I struggle to keep my feet on the ground since my load lifts me up into the air.[78]

Through this exchange Jung demonstrates the tremendous power that Fantasy has, if allowed to work its enchantment. He writes, “Thus my God found salvation. He was saved precisely by what one would actually consider fatal, namely by declaring him a figment of the imagination.”[79]

Significant in itself, this scene of carrying one who ought to be heavy yet is somehow light also has a resemblance to one of the most moving moments in The Lord of the Rings, when Sam and Frodo are struggling up the treacherous slopes of Mount Doom.

“Now for it! Now for the last gasp!” said Sam as he struggled to his feet. He bent over Frodo, rousing him gently. Frodo groaned; but with a great effort of will he staggered up; and then he fell upon his knees again. He raised his eyes with difficulty to the dark slopes of Mount Doom towering above him, and then pitifully he began to crawl forward on his hands.

Sam looked at him and wept in his heart, but no tears came to his dry and stinging eyes. “I said I’d carry him, if it broke my back,” he muttered, “and I will!”

“Come, Mr. Frodo!” he cried. “I can’t carry it for you, but I can carry you and it as well. So up you get! Come on, Mr. Frodo dear! Sam will give you a ride. Just tell him where to go, and he’ll go.”

As Frodo clung upon his back, arms loosely about his neck, legs clasped firmly under his arms, Sam staggered to his feet; and then to his amazement he felt the burden light. He had feared that he would have barely strength to lift his master alone, and beyond that he had expected to share in the dreadful dragging weight of the accursed Ring. But it was not so. Whether because Frodo was so worn by his long pains, wound of knife, and venomous sting, and sorrow, fear, and homeless wandering, or because some gift of final strength was given to him, Sam lifted Frodo with no more difficulty than if he were carrying a hobbit-child pig-a-back in some romp on the lawns or hayfields of the Shire. He took a deep breath and started off.[80]

Perhaps one of the most profound areas in which the fantasy visions, and respective world views, of Jung and Tolkien overlap is around the nature of evil. They both had a deep understanding of the nature of evil, and were able to articulate its presence in the world in a way that demonstrates the importance of confronting that evil and going into its depths on behalf of personal and collective transformation. Yet not only do Tolkien and Jung share a similar understanding of the workings of evil, they also share uncannily similar depictions of evil nature in both their art and writing. Within The Lord of the Rings, the clearest view we are given of the Dark Lord is his great Eye, “an image of malice and hatred made visible . . . the Eye of Sauron the Terrible [that] few could endure.”[81] Frodo has two separate visions of the Eye, each more terrifying than the last. The first is while gazing into the Mirror of Galadriel in the woods of Lothlórien.

But suddenly the Mirror went altogether dark, as dark as if a hole had opened in the world of sight, and Frodo looked into emptiness. In the black abyss there appeared a single Eye that slowly grew, until it filled nearly all the Mirror. So terrible was it that Frodo stood rooted, unable to cry out or to withdraw his gaze. The Eye was rimmed with fire, but was itself glazed, yellow as a cat’s, watchful and intent, and the black slit of its pupil opened on a pit, a window into nothing.

Then the Eye began to rove, searching this way and that; and Frodo knew with certainty and horror that among the many things that it sought he himself was one.[82]

The second exposure to the Eye of Sauron that Frodo endures is upon Amon Hen, the Hill of Seeing:

All hope left him. And suddenly he felt the Eye. There was an eye in the Dark Tower that did not sleep. He knew that it had become aware of his gaze. A fierce eager will was there. It leaped towards him; almost like a finger he felt it, searching for him. Very soon it would nail him down, know just exactly where he was.[83]

These powerful depictions of the piercing gaze of evil also entered into Jung’s Red Book visions, in both image and word. Tolkien did many illustrations of the Eye of Sauron, showing a red iris with a hard black pupil. Within the illuminated letter on the first page of the Liber Secundus, the second section of Jung’s Red Book, is a nearly identical illustration: a red eye with a hollow black pupil in its center (see Figures 12 and 13). Yet Jung also writes further into The Red Book,

Nothing is more valuable to the evil one than his eye, since only through his eye can emptiness seize gleaming fullness. Because the emptiness lacks fullness, it craves fullness and its shining power. And it drinks it in by means of its eye, which is able to grasp the beauty and unsullied radiance of fullness. The emptiness is poor, and if it lacked its eye it would be hopeless. It sees the most beautiful and wants to devour it in order to spoil it.[84]

The eye that symbolizes evil is an eye that looks only outward; it does not look inward, it does not self-reflect. The eye as symbol of evil cautions against the refusal to look deep into one’s innermost self, to face the Shadow within. If one only looks outward one becomes subsumed by that Shadow; it is all the world can see although the eye may be blind to it from within. Indeed, both Jung and Tolkien even used the term Shadow to refer to this darkness that must be faced and reflected upon.

“He who journeys to Hell also becomes Hell: therefore do not forget from whence you come . . . do not be heroes . . .” Jung writes in The Red Book.[85] Indeed, the two Hobbits who journey into Hell, into Mordor, are not Heroes. They are but simple folk who do the task that is at hand, that has been set before them by the greater powers of the world. But Frodo succumbs to the Hell into which he enters; at the final moment when he is meant to throw the One Ring into the Cracks of Doom, within the heart of the volcano Orodruin, Mount Doom, he cannot do it. He takes the Ring for himself.

Then Frodo stirred and spoke with a clear voice, indeed with a voice clearer and more powerful than Sam had ever heard him use, and it rose above the throb and turmoil of Mount Doom, ringing in the roof and walls.

“I have come,” he said. “But I do not choose now to do what I came to do. I will not do this deed. The Ring is mine!” And suddenly, as he set it on his finger, he vanished from Sam’s sight.[86]

Frodo has, in that pivotal moment, become the evil he had set out to destroy. But it is only through that act, and through his ultimate sacrifice, that the quest can in the end be achieved. In the same section of The Red Book in which Jung writes of the eye of evil, he also writes, “the scene of the mystery play is the heart of the volcano.”[87] The moment of transformation, the unexpected turn that Tolkien calls the eucatastrophe, takes place in the fiery heart of the volcanic underworld.

A form of art that Jung found to have particular significance in the psychological journey was the mandala, a circular and quadratic emblem that he came to recognize as a symbol of the Self. Without knowing what at first he was doing, Jung drew his first mandala on January 16, 1916 (see Figure 14).[88] He came to understand that the mandala form represented “Formation, transformation, the eternal mind’s eternal recreation.”[89] In Tolkien’s artwork I did not expect to also find drawings of mandalas, and yet it seems that towards the end of his life he would wile away the time drawing ornate patterns on the backs of envelopes and on newspapers as he solved the crossword.[90] Many of these emblems, which he later designated as Elvish heraldic devices symbolizing individual characters within his mythology, were mandalic in form (see Figure 15), as were some others of his more complete drawings (see Figure 16). Yet another interesting quality of Tolkien’s art was that he often designed his pictures around a central axis.[91] If one were to imagine moving from the sideways perspective portrayed in the drawing to a bird’s eye view from above, these illustrations of Tolkien’s quite likely would resemble a mandala (see Figures 17 and 18).

“If the encounter with the shadow is the ‘apprentice-piece’ in the individual’s development, then that with the anima is the ‘master-piece.’”[92] Jung wrote these words in reference to his own visionary experiences, as well as the experiences of the patients with whom he worked. We have already explored parallels in Jung’s and Tolkien’s encounters with the Shadow. But what of the encounter with Anima? The Anima for Jung is the female personification of the soul of a man, and the Animus is the male personification of the soul of a woman. Anima figures can take many forms, of course based upon the psychology of each individual. For Jung, one of the personifications of his Anima whom he encountered in the physical world at a young age was a girl he met briefly while walking in the Swiss mountains. As they began to descend the mountain side by side, he said “. . . a strange feeling of fatefulness crept over me. ‘She appeared at just this moment,’ I thought to myself, ‘and she walks along with me as naturally as if we belonged together.’”[93] Reflecting later on the encounter, he wrote, “. . . seen from within, it was so weighty that it not only occupied my thoughts for days but has remained forever in my memory, like a shrine by the wayside.”[94] This girl was one of several women who represented an Anima image for Jung, the female symbol of his soul.

The last story that Tolkien ever wrote in his life was called Smith of Wootton Major. It is a short story of a man who, as a child, is given a fay star, an emblem from the realm of Faërie, that grants him passageway into that enchanted world. On one of his journeys through Faërie this man encounters, in a high mountain meadow, a beautiful dancing maiden.

On the inner side the mountains went down in long slopes filled with the sound of bubbling waterfalls, and in great delight he hastened on. As he set foot upon the grass of the Vale he heard elven voices singing, and on a lawn beside a river bright with lilies he came upon many maidens dancing. The speed and the grace and the ever-changing modes of their movements enchanted him, and he stepped forward towards their ring. Then suddenly they stood still, and a young maiden with flowing hair and kilted skirt came out to meet him.

She laughed as she spoke to him, saying: “You are becoming bold, Starbrow, are you not? Have you no fear what the Queen might say, if she knew of this? Unless you have her leave.” He was abashed, for he became aware of his own thought and knew that she read it: that the star on his forehead was a passport to go wherever he wished; and now he knew that it was not. But she smiled as she spoke again: “Come! Now that you are here you shall dance with me”; and she took his hand and led him into the ring.

There they danced together, and for a while he knew what it was to have the swiftness and the power and the joy to accompany her. For a while. But soon as it seemed they halted again, and she stooped and took up a white flower from before her feet, and she set it in his hair. “Farewell now!” she said. “Maybe we shall meet again, by the Queen’s leave.”[95]

Although clearly of a fictional nature, Smith’s encounter with the Elven-maiden has certain resemblances to the young girl with whom Jung walked in the Swiss mountains, and perhaps she had a similar significance to each of them too. Indeed, Jung even wrote in The Red Book that he sees “the anima as elf-like; i.e. only partially human.”[96]During Smith’s final visit to Faërie his most profound meeting occurs:

On that visit he had received a summons and had made a far journey. Longer it seemed to him than any he had yet made. He was guided and guarded, but he had little memory of the ways that he had taken; for often he had been blindfolded by mist or by shadow, until at last he came to a high place under a night-sky of innumerable stars. There he was brought before the Queen herself. She wore no crown and had no throne. She stood there in her majesty and her glory, and all about her was a great host shimmering and glittering like the stars above; but she was taller than the points of their great spears, and upon her head burned a white flame. She made a sign for him to approach, and trembling he stepped forward. A high clear trumpet sounded, and behold! they were alone.

He stood before her, and he did not kneel in courtesy, for he was dismayed and felt that for one so lowly all gestures were in vain. At length he looked up and beheld her face and her eyes bent gravely upon him; and he was troubled and amazed, for in that moment he knew her again: the fair maid of the Green Vale, the dancer at whose feet the flowers sprang. She smiled seeing his memory, and drew towards him; and they spoke long together, for the most part without words, and he learned many things in her thought, some of which gave him joy, and others filled him with grief. . . .

Then he knelt, and she stooped and laid her hand on his head, and a great stillness came upon him; and he seemed to be both in the World and in Faery, and also outside them and surveying them, so that he was at once in bereavement, and in ownership, and in peace. When after a while the stillness passed he raised his head and stood up. The dawn was in the sky and the stars were pale, and the Queen was gone. Far off he heard the echo of a trumpet in the mountains. The high field where he stood was silent and empty: he knew that his way now led back to bereavement.[97]

The encounter with the Queen of Faery may be as significant as the encounter with the Anima, and perhaps that is who the Queen of Faery is. Smith of Wootton Major is considered to be something of an autobiographical tale, or as close as Tolkien would ever come to writing one. Perhaps he is writing of his own encounter with his Anima, or rather an encounter with the archetype of Anima as present in all myths, within the individual human soul and in the mythic dimensions of the cosmos.

Jung identified what he called the “transcendent function” as that which bridges the conscious and the unconscious. The transcendent function takes the form of a symbol that transcends time and conflict, that is common to both the conscious and the unconscious, and that offers the possibility of a new synthesis between them.[98] In The Red Book Jung writes of the power of such a symbol:

The symbol is the word that goes out of the mouth, that one does not simply speak, but that rises out of the depths of the self as a word of power and great need and places itself unexpectedly on the tongue. . . . If one accepts the symbol, it is as if a door opens leading into a new room whose existence one previously did not know.[99]

Symbols are present in myths and stories, and in the living visions of the creative imagination. Symbolic, archetypal story can open doorways between the conscious and the unconscious, between this world and the enchanted realm of Faërie. “Such stories,” Tolkien writes, “open a door on Other Time, and if we pass through, though only for a moment, we stand outside our own time, outside Time itself maybe.”[100] Perhaps Fantasy, or Imagination itself, are the transcendent function of which Jung speaks.

In reading Jung’s and Tolkien’s Red Books side by side and seeing the profound similarities in their experiences, and in the writing and artwork produced from those experiences, I came to feel that they may have been entering into the same realm. Whether we call it Faërie, or the collective unconscious, or the Imagination, both men seemed to be crossing a threshold and walking down parallel and even overlapping paths in the same kingdom. Jung writes, “The collective unconscious is common to all; it is the foundation of what the ancients called the ‘sympathy of all things’.”[101] It is the fertile ground from which grows the Tree of Tales, it is the wellspring of the Imagination born anew in each creative person. Tolkien too had a sense that this place in which he witnessed his stories was the unconscious. In a letter to W.H. Auden, Tolkien writes,

I daresay something had been going on in the “unconscious” for some time, and that accounts for my feeling throughout, especially when stuck, that I was not inventing but reporting (imperfectly) and had at times to wait till “what really happened” came through.[102]

I have come to believe that Imagination is a place, a realm, that is both inner and outer. The Imagination is not merely a human capacity, a function of the mind or the workings of the brain. It is a place that can be accessed through human capacity, through creativity, but Imagination extends far beyond human capacity as well. It is a world as infinite as the physical one in which we daily dwell.

Now that the particular leg of this journey is drawing to a close, we can ask how Jung and Tolkien can inform each other’s works. Jung advised that each person could make their own Red Book from the Fantasies that arise through the practice of active imagination. He said to return to your Red Book like you would to a sanctuary or cathedral, for your soul is within its pages.[103] The Red Book that Tolkien created for himself he gave to the world in the form of The Lord of the Rings. It is a text that is treated by many as a sacred text, one to be returned to year after year, or read aloud with loved ones. Why is that? Because The Lord of the Rings, like Jung’s Red Book, is an invitation to enter the realm of Imagination. It is an invitation to find our own stories and learn to tell them. Indeed, when Tolkien was first conceiving of his Middle-Earth legendarium, at the same time that Jung was writing down the visions of his Red Book, he saw it as a great mythological arc in which space would be left for others to take it further with their own art and stories. He once wrote, in his usual self-deprecating tone, “I would draw some of the great tales in fullness, and leave many only placed in the scheme, and sketched. The cycles should be linked to a majestic whole, and yet leave scope for other minds and hands, wielding paint and music and drama. Absurd.”[104]

Sonu Shamdasani, the historian of psychology who took on the great task of editing Liber Novus, captures succinctly and elegantly what Jung’s and Tolkien’s respective Red Books are inviting each one of us to do. He writes, “What was most essential was not interpreting or understanding the fantasies, but experiencing them.”[105]

Works Cited

Carpenter, Humphrey. J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000.

Flieger, Verlyn. A Question of Time: J.R.R. Tolkien’s Road to Faërie. Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 1997.

Hammond, Wayne G. and Christina Scull. J.R.R. Tolkien: Artist & Illustrator. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000.

Jung, C.G. “Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious.” In Collected Works. Vol. 9, i. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1959.

–––––. Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Edited by Aniela Jaffé. Translated by Richard and Clara Winston. New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1989.

–––––. The Red Book: Liber Novus. Edited by Sonu Shamdasani. Translated by Mark Kyburz, John Peck, and Sonu Shamdasani. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009.

Owens, Lance. “Lecture I: The Discovery of Faërie.” In J.R.R. Tolkien: An Imaginative Life. Salt Lake City, UT: Westminster College, 2009. http://gnosis.org/tolkien/lecture1/index.html.

–––––. “Tolkien, Jung, and the Imagination.” Interview with Miguel Conner. AeonBytes Gnostic Radio, April 2011. http://gnosis.org/audio/Tolkien-Interview-with-Owens.mp3.

Samuels, Andrew, Bani Shorter and Fred Plant. A Critical Dictionary of Jungian Analysis. New York, NY: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986.

Tarnas, Richard. Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View. New York, NY: Viking Penguin,

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Edited by Humphrey Carpenter, with Christopher Tolkien. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000.

–––––. The Lord of the Rings. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1994.

–––––. “On Fairy-Stories.” In The Monsters and the Critics. Edited by Christopher Tolkien. London, England: HarperCollins Publishers, 2006.

–––––. The Silmarillion. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2001.

–––––. “Smith of Wootton Major.” In Tales from the Perilous Realm. London, England: HarperCollinsPublishers, 2002.

[1] C.G. Jung, The Red Book: Liber Novus, ed. Sonu Shamdasani, trans. Mark Kyburz, et al. (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009), 311.

[2] J.R.R. Tolkien, “On Fairy-Stories” in The Monsters and the Critics, ed. Christopher Tolkien (London, England: HarperCollins Publishers, 2006), 145.

[3] J.R.R. Tolkien, qtd. in Humphrey Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography (New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000), 97.

[4] Tolkien, qtd. in Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography, 98.

[5] Lance Owens, “Lecture III: Tolkien and the Imaginative Tradition,” in J.R.R. Tolkien: An Imaginative Life, (Salt Lake City, UT: Westminster College, 2009), http://gnosis.org/tolkien/lecture3/index.html.

[6] Ulrich Hoerni, “Preface,” in Jung, The Red Book, VIII.

[7] Jung, The Red Book, 200.

[8] Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull, J.R.R. Tolkien: Artist & Illustrator (New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000), 40.

[9] Hammond and Scull, J.R.R. Tolkien: Artist & Illustrator, 50.

[10] Ibid, 19.

[11] Lance Owens, “Tolkien, Jung, and the Imagination,” interview with Miguel Conner, AeonBytes Gnostic Radio, April 2011, http://gnosis.org/audio/Tolkien-Interview-with-Owens.mp3.

[12] C.G. Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, ed. Aniela Jaffé, trans. Richard and Clara Winston (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1989), 199.

[13] Richard Tarnas, Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View (New York, NY: Viking Penguin, 2006), 365.

[14] Tarnas, Cosmos and Psyche, 355.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid, 93.

[18] Tarnas, Cosmos and Psyche, 356.

[19] Sonu Shamdasani, “Introduction,” in Jung, The Red Book, 204.

[20] Tarnas, Cosmos and Psyche, 365.

[21] Hoerni, “Preface,” in Jung, The Red Book, IX.

[22] Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, 33.

[23] Ibid, 34.

[24] Ibid, 87.

[25] Ibid, 72.

[26] Ibid, 45.

[27] Ibid, 66.

[28] Tolkien, “On Fairy-Stories,” 116.

[29] Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography, 13.

[30] Jung, The Red Book, 196.

[31] Jung, The Red Book, 203.

[32] Hammond and Scull, J.R.R. Tolkien: Artist & Illustrator, 40.

[33] Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, 175.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography, 31.

[36] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, ed. Humphrey Carpenter, with Christopher Tolkien (New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000), 347.

[37] Lance Owens, “Lecture I: The Discovery of Faërie,” in J.R.R. Tolkien: An Imaginative Life, (Salt Lake City, UT: Westminster College, 2009), http://gnosis.org/tolkien/lecture1/index.html.

[38] Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography, 193.

[39] Hoerni, “Preface,” in Jung, The Red Book, VIII.

[40] Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, 179.

[41] Owens, “Lecture I: The Discovery of Faërie.”

[42] Verlyn Flieger, A Question of Time: J.R.R. Tolkien’s Road to Faërie (Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 1997), 260, n. 2.

[43] Hammond and Scull, J.R.R. Tolkien: Artist & Illustrator, 40.

[44] Owens, “Lecture I: The Discovery of Faërie.”

[45] Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography, 57-8.

[46]Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography, 59.

[47] Owens, “Lecture I: The Discovery of Faërie.”

[48] Mark Kyburz, John Peck, and Sonu Shamdasani, “Translators’ Note,” in Jung, The Red Book, 222.

[49] Owens, “Tolkien, Jung, and the Imagination,” interview with Miguel Conner.

[50] Owens, “Lecture I: The Discovery of Faërie.”

[51] Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography, 44.

[52] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1994), II, i, 227.

[53] Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography, 72.

[54] Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography.

[55] Ibid, 79.

[56] Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, 227.

[57] Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography, 83.

[58]Ibid, 99.

[59] Shamdasani, “Introduction,” in Jung, The Red Book, 202.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, 177-8.

[63] Andrew Samuels, et al., A Critical Dictionary of Jungian Analysis (New York, NY: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986), 58.

[64] Samuels, et al., A Critical Dictionary of Jungian Analysis, 59.

[65] Tolkien, “On Fairy-Stories,” 135.

[66] Tolkien, “On Fairy-Stories,” 144.

[67] Ibid, 139, n. 2.

[68] Hammond and Scull, J.R.R. Tolkien: Artist & Illustrator, 64.

[69] Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, 67-8.

[70] Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography, 30.

[71] Flieger, A Question of Time, 165.

[72] Ibid, 166.

[73] Jung, The Red Book, 274.

[74] Tolkien, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, 213.

[75] Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, II, vii, 354.

[76] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Silmarillion (New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2001), 280.

[77] Tolkien, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, 361.

[78] Jung, The Red Book, 282.

[79] Ibid, 283.

[80] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1994), VI, iii, 919-20.

[81] Tolkien, The Silmarillion, 280-1.

[82] Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, II, vii, 355.

[83] Ibid, II, x, 392.

[84] Jung, The Red Book, 289.

[85] Jung, The Red Book, 244.

[86] Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, VI, iii, 924.

[87] Jung, The Red Book, 247.

[88] Ibid, 206.

[89] Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, 221.

[90] Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography, 242.

[91] Hammond and Scull, J.R.R. Tolkien: Artist & Illustrator, 149.

[92] C.G. Jung, “Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious,” in Collected Works, vol. 9, i (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1959), 29.

[93] Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, 79.

[94] Ibid, 80.

[95] J.R.R. Tolkien, “Smith of Wootton Major,” in Tales from the Perilous Realm (London, England: HarperCollinsPublishers, 2002), 160-1.

[96] Jung, The Red Book, 198, n. 39.

[97] Tolkien, “Smith of Wootton Major,” 162-4.

[98] Samuels, et al., A Critical Dictionary of Jungian Analysis, 150.

[99] Jung, The Red Book, 311.

[100] Tolkien, “On Fairy-Stories,” 128-9.

[101] Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, 138.

[102] Tolkien, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, 212.

[103] Jung, The Red Book, 216.

[104] Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography, 98.

[105] Jung, The Red Book, 217.

Great stories become symbols as they are encountered again and again by successive generations, as they are read in the context of currently unfolding lives. Stories become a part of the ecology in which they are told, participating in shaping the cultural landscape and being reshaped by it as well. Homer, Plato, Dante, Shakespeare—these are but a few of the authors whose stories have withstood the slow wearing and reshaping of the passing river of time; they are narratives that have become changing symbols for those who have taken them up in their own time. J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-Earth legendarium, principally his Lord of the Rings epic, has been called by several scholars a myth for our time, a symbol of the age in which we live. As one Tolkien scholar writes, The Lord of the Rings is a tale that “will bear the mind’s handling, and it is a book that acquires an individual patina in each mind that takes it up, like a much-caressed pocket stone or piece of wood.”[1] Such is the gift of a story written not as prescriptive allegory, but rather as what Tolkien preferred to see as “history, true or feigned, with its various applicability to the thought and experience of readers.”[2] It is the flexible applicability of Tolkien’s narrative that allows it to be adapted and molded according to the needs and desires of the generations encountering it, providing a symbolic foil to the world in which it is being retold.

Tolkien began writing his mythology during a time of rapid transformation in Europe, as he witnessed increasing industrialization overwhelm the rural landscape of his native England. His stories carry much of the melancholy rendered by this loss of ecological beauty, and seem to plant seeds of warning for upcoming generations as more and more of the Earth’s landscapes are being turned to solely human uses. The ecological awareness at the heart of Tolkien’s world may contribute to its particular applicability to the current time period in which we face massive anthropogenic ecological destruction. Methods of engagement with the ecological crisis are innumerably diverse, a reflection of the broad scale of the problems with which the Earth community is challenged. Philosophical approaches to ecology and environmentalism have sought different means of engaging with the very concept of nature, as well as the dualisms created between human and nature, self and other, subject and object, that have contributed to making the Earth crisis what it is. Can Tolkien’s tales of Middle-Earth provide a symbolic mirror for some of these approaches, from ecofeminism, to dark ecology, to process ethics? By bringing such frameworks into dialogue with narrative, can new concepts be born through their interminglings and diversions?

This study of Middle-Earth as an ecological foil will go in several different directions, although they will all address overlapping issues related to how concepts of unity and difference play significant roles in the human relationship to the Earth. I will be using Tolkien’s narrative in two ways: on the one hand, by looking at it from the outside to see how it might change the engagement of the reader—as a participant in an imaginal world—with the primary world in which she lives; and on the other hand, by diving into the world itself and studying the characters directly as examples of individuals engaging in different ways with their own world. I will first explore the role art plays in shaping the human relationship with the Earth, seeing how art can both cultivate a sense of identity with the natural world, but also how it can give a clearer view of the diversity and inherent difference in that world. Crossing the threshold and entering into Middle-Earth itself we can continue exploring themes of identity and difference, remoteness and entanglement, duality and unity, by bringing such thinkers as Timothy Morton, Val Plumwood, Pierre Hadot, Slavov Zizek, and Alfred North Whitehead into dialogue with Tolkien’s work.

Imaginal worlds and the stories which take place within them can provide what Tolkien calls a “recovery,” a “regaining of a clear view.”[3] He goes on to elaborate what such a clear view can offer, saying:

I do not say “seeing things as they are” and involve myself with the philosophers, though I might venture to say “seeing things as we are (or were) meant to see them”—as things apart from ourselves. We need, in any case, to clean our windows; so that the things seen clearly may be freed from the drab blur of triteness or familiarity—from possessiveness.[4]

Although he mentions not wanting to involve himself with the philosophers, for the purpose of this essay I will be drawing Tolkien’s narratives into philosophical dialogue. The ecophenomenologist Neil Evernden offers a complementary, although somewhat reoriented, view to Tolkien’s on the role that art and the humanities can play in ecology: quoting Northrop Frye to make his point, Evernden says, “the goal of art is to ‘recapture, in full consciousness, that original lost sense of identity with our surroundings, where there is nothing outside the mind of man, or something identical with the mind of man.’”[5] Evernden’s perspective dissolves the boundary between the human and the natural world, whereas Tolkien’s sharpens awareness that there is a surrounding world that cannot be possessed by the human. Both perspectives, however, lead to a reorientation of values in which the natural world cannot become forgotten or taken for granted. They both call forth a sense of wonder.

The French philosopher Pierre Hadot points towards how art can create continuity between humanity and nature, offering another perspective for regaining the clear view of which Tolkien speaks:

If . . . people consider themselves a part of nature because art is already present in it, there will no longer be opposition between nature and art; instead, human art, especially in its aesthetic aspect, will be in a sense the prolongation of nature, and then there will no longer be any relation of dominance between nature and mankind.[6]

Art offers to the spectator the possibility of becoming a participant, to engage at a personal level with the subject as portrayed by the work of art. The human subject can no longer encounter the other in the art as solely objective for, as Evernden writes, “The artist makes the world personal—known, loved, feared, or whatever, but not neutral.”[7] For Tolkien, art is what gives to the creations of the imagination “the inner consistency of reality”[8] that allows both the designer and spectator to enter into the created world. We have the possibility of entering fully into a world such as Tolkien’s and seeing its applicability to our own world, which is what makes it such a potent symbol for our own actions.

Entering into Middle-Earth we find ourselves in the Shire, the quiet, sheltered landscape inhabited by Hobbits. The Shire is insolated from the outside world, its inhabitants peacefully oblivious to the wider world, its borders guarded unbeknownst to the Hobbits by human Rangers of the North. The Lord of the Rings can be seen as a literary example and metaphor of overcoming the dualism between self and other, human and nature, and subject and object. It tells the story of how four Hobbits leave their isolated world—and also world view—of the Shire to journey into the diverse landscapes of Middle-Earth and encounter the many peoples shaped by those lands. They realize they are but one small part of a larger, diverse ecology of beings. As Morton writes in his book Ecology Without Nature,

The strangeness of Middle-Earth, its permeation with others and their worlds, is summed up in the metaphor of the road, which becomes an emblem for narrative. The road comes right up to your front door. To step into it is to cross a threshold between inside and outside.[9]

Morton is quite critical of Tolkien, seeing Middle-Earth as an “elaborate attempt to craft a piece of kitsch,” a closed world where “however strange or threatening our journey, it will always be familiar” because “it has all been planned out in advance.”[10] This criticism is, in many ways, the exact opposite of what Tolkien describes the very aim of fantasy to be, to free things ‘from the drab blur of triteness or familiarity—from possessiveness.’ Is this an indication that Tolkien has failed in his project, or rather that Morton is misreading what it is that Tolkien is attempting to do? Morton begins his analysis of Middle-Earth by saying,

The Shire . . . depicts the world-bubble as an organic village. Tolkien narrates the victory of the suburbanite, the “little person,” embedded in a tamed yet natural-seeming environment. Nestled into the horizon as they are in their burrows, the wider world of global politics is blissfully unavailable to them.[11]

In many ways this is a true characterization of the Shire at the start of the tale. There is an idyllic pastoralism to the Shire that is cherished by many of Tolkien’s readers, but it is also a realm of sheltered innocence as Morton points out, a Paradise before the Fall. However, by substituting this image of the Shire for the whole of Middle-Earth, Morton misses an essential aspect of the narrative: the Hobbits must depart from the Shire and encounter the strangeness and diversity of the larger world. The Hobbits, who may start out as ‘little suburbanites,’ cannot accomplish the tasks asked of them without first being transformed through the suffering and awakening that comes from walking every step of their journey. To return to Morton’s quote about the Road, once the ‘threshold between inside and outside’ has been crossed, the traveler cannot return to his former innocence. It is a shift in world view. The Hobbits can never return to the solipsistic world that existed prior to that crossing. This is an essential move that is also being asked of the human species in our own time; to cross out of our anthropocentric world view to encounter the great and imperiled diversity of the wider world.

While the Hobbits’ journey can serve as a metaphor for the journey the human species is being called to take—to awaken to the crisis at hand and leave our anthropocentric world view—The Lord of the Rings can be read symbolically from another perspective in which different characters represent alternative approaches to the natural world that have been taken by humanity over the course of history. These differing approaches have been laid out by Pierre Hadot in his “essay on the history of the idea of nature,” The Veil of Isis. Using mythic terms, these are what Hadot calls the Orphic and Promethean attitudes:

Orpheus thus penetrates the secrets of nature not through violence but through melody, rhythm, and harmony. Whereas the Promethean attitude is inspired by audacity, boundless curiosity, the will to power, and the search for utility, the Orphic attitude, by contrast, is inspired by respect in the face of mystery and disinterestedness.[12]

The three primary methods of the Promethean attitude, according to Hadot, are experimentation, mechanics, and magic, each of which seek to manipulate nature for some specific end. In Middle-Earth the Promethean approach is used by the Dark Lord Sauron, and later by the wizard Saruman, as they each seek to employ technology to gain power and dominion over others. Hadot writes of the Promethean attitude: “Man will seek, through technology, to affirm his power, domination, and rights over nature.”[13] As Treebeard says of Saruman, “He is plotting to become a Power. He has a mind of metal and wheels; and he does not care for growing things, except as far as they serve him for the moment.”[14] Saruman’s drive for power is a mere shadow and an echo of Sauron’s: the emblematic symbol of the power of technology in The Lord of the Rings is of course the One Ring itself, a device or machine that takes away the free will of those who use it.