“Perhaps the path or method of re-search done with soul in mind is simply a recognition that all our acts of knowing are attempts at remembering what we once knew but have forgotten. Perhaps all our attempts at re-search are sacred acts whose deep motive is salvation or redemption. Maybe all our re-search reenacts the Gnostic dream of the fall of soul into time and its desire to return home.”

– Robert Romanyshyn[1]

The journey of this dissertation began with the intuition of a synchronicity. The first time I beheld The Red Book of C.G. Jung I felt an echo in my memory: J.R.R. Tolkien also had a Red Book, The Red Book of Westmarch, that he claimed was the supposedly fictional source from which he had translated his stories The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Yet, besides the titles, there was no reason to suppose any similarity existed between the two Red Books; no reason except that my intuition was telling me to look further, to find out if there might perhaps be more in common between these seemingly disparate works than would ordinarily be expected.

As I started preliminary research on this topic I began to find uncanny similarities between many of the images and experiences recorded in Jung’s Red Book and several of the stories and pieces of artwork from Tolkien’s oeuvre. Furthermore, I found that both men were having experiences of what Jung came to call “active imagination” beginning in the same year—1913—and continuing for several years thereafter. The images from this time period provided the seminal material that both men spent the next forty years developing in their work. The further I investigated, the more the similarities revealed themselves, until I began to question what the implications were of the synchronicity of the two Red Books. If Jung and Tolkien were simultaneously having experiences of active imagination that led them each to create art and writing with many similarities in style and content, what did this indicate about the sources of these experiences? If these findings were not to be dismissed as mere coincidence, then what did they imply about the nature of imagination? Such thoughts led me to the formulation of the primary research question of my dissertation: What implications might the imaginal experiences of Jung and Tolkien have for the modern disenchanted world view that has led to our current ecospiritual crisis, and how might a greater understanding of imagination lead to a shift in consciousness? My preliminary thesis statement is that the experiences of these two men point to the ontological reality of an imaginal realm, which holds significant implications for overturning the disenchanted world view that has contributed greatly to the ecological crisis.

Because of the nature of my inquiry, and the manner in which the research topic revealed itself, the methodological approach to this dissertation must be one that affirms the importance of imagination and intuition in the research process. Therefore I will be using an alchemical hermeneutics, as developed by Robert Romanyshyn, as my primary research methodology because it is an approach that aims to “keep soul in mind,”[2] and emphasizes the importance of imagination, intuition, feelings, dreams, synchronicity, and the myriad other expressions of the unconscious that emerge in the research process. Alchemical hermeneutics is what Romanyshyn calls an imaginal approach to research, an approach that complements other methods, rather than seeking to replace them.[3] Thus, I will be taking a mixed methods approach to this research topic, with each method filtered through the imaginal lens of alchemical hermeneutics.

“When one designs a method,” Romanyshyn writes, “one is mapping out the journey that one will take from that place of not knowing one’s topic to that place of coming to know it.”[4] For my dissertation research I will be employing an array of methods to address the multiple levels of the topic: literary, artistic, biographical, historical, and archetypal analysis, which will each be engaged from an imaginal research perspective. If alchemical hermeneutics is the path mapped out for my research journey, I see these different forms of comparative analysis as the supplies I have in my pack to aid me along the way. Each of these methods will come in handy at different points on the journey, depending on what the terrain of the research is at the current moment.

“Method is also who the researcher is in the work, who he or she is as he or she continuously opens a path into a work. Method is an attitude that pervades the whole process of research as a journey.”[5] My choice of an alchemical hermeneutics will not only shape the results of my research, it will shape me along the way. According to Romanyshyn, “dissertation writing can become an aspect of the individuation process.”[6] As I am transformed by the process of researching and writing, my methodological approach will be transformed as well. This is what Romanyshyn refers to as the hermeneutic circle:

Within the embrace of this circle of understanding, the knower approaches a text with some foreknowledge of it, which in turn is questioned and challenged and amplified by the text, thereby transforming the knower who returns to the text with a different understanding of it.[7]

For example, when I first approached Jung’s Red Book, I had already been steeped for a decade and a half in the stories, languages, and images of Tolkien’s world of Middle-Earth. This reserve of knowledge, which I was already shaped by, in turn shaped how I approached my initial reading of Jung’s Red Book. Yet, after delving more deeply into the content of Jung’s imaginal experiences, the way in which I viewed Tolkien’s stories, and his process of creating them, began to shift as well. As Romanyshyn points out, “the topic chooses the researcher as much as, and perhaps even more than, he or she chooses it.”[8] I had the sense that something in the material was asking me to explore it, although the calling seemed to be taking place below the conscious level. One way in which alchemical hermeneutics differentiates from traditional hermeneutics is that is seeks to bring the unconscious of the researcher into the process of research itself. Romanyshyn describes this recursive dialogue between the researcher and the material as the hermeneutic spiral:

One task of an alchemical hermeneutic method is to deepen the hermeneutic circle by twisting it into a spiral. The researcher, then, follows the arc of the hermeneutic circle, but in such a way that the engagement of the two takes into account the unconscious aspects of the researcher and the work.[9]

The imaginal approach to research is particularly well-suited to this topic because it seeks to recreate through methodology Jung’s and Tolkien’s own imaginal methods in producing their material. Romanyshyn writes, “In a sense, we might say that alchemical hermeneutics is the offspring of the encounter between the tradition of hermeneutics and depth psychology.”[10]

Before unpacking further the pertinent aspects of alchemical hermeneutics, I would like to look at the more specific methods I will be using throughout this research journey. As mentioned previously, I will be using literary, artistic, biographical, historical, and archetypal analysis, depending on which aspects of Jung and Tolkien I am studying. Both men expressed themselves primarily through writing, therefore I will be using literary analysis to compare the texts they each produced. To narrow the scope of which texts I will analyze, I am focusing on material directly related to or produced by imaginal means—in Tolkien’s case the stories, poems, and languages that he composed, and in Jung’s case the narrations of his experiences of active imagination, recorded primarily in The Red Book. I will be comparing the content of these texts, and at times the style, although the fact that they were originally written in different languages—English and German, respectively—will have to be taken into account.

Besides the common name of The Red Book, what originally drew my attention to the potential similarities between Jung’s and Tolkien’s work was a resonance in the style and content of their artwork. Not only were there common images of dragons, cosmic trees, eyes, and mandalas, but there were deeper similarities that I could feel intuitively but were not explicitly on the surface. These were images that seemed to be expressing the entrance into an internal world, an imaginal world, the realm of psyche. An analysis of these images has to take place on multiple levels. On the one hand, the images can be analyzed for specific content, compared to each other as well as to other artwork produced at the time. Is the resonance in style particular to Jung and Tolkien, or does it reflect a larger artistic style of that cultural period in history? On the other hand, the artwork can also be analyzed symbolically, not only when there are shared appearances between Tolkien’s and Jung’s art, but also when the images differ aesthetically yet might symbolically be pointing toward a congruent meaning.

Hermeneutics is the art of interpreting and coming to understand symbols as expressed in texts and images. An alchemical hermeneutics seeks to approach this act of interpretation by recognizing that a symbol can never be exhausted, for the very nature of a symbol is that it presences what is absent. Romanyshyn writes,

Interpretation is always a “failure” because what is present in the symbol remains haunted by what is absent. . . . Interpretation at the level of soul is not just about deciphering a hidden meaning, it is also about a hunger for the ordinary presence that still lingers as an absent presence.[11]

In my approach to the images created by Jung and Tolkien, both in text and in art, I am not only reading what the symbols contained therein are explicitly communicating, but also what is implicit in their very existence. I am asking of these symbols not only what they are expressing, but why. What meanings do these symbols point towards? The meaning of symbols can unfold eternally: “Alchemical hermeneutics,” Romanyshyn writes, “is not, therefore, only about arriving at meaning as a solution. It is also about the continuous dissolution of meaning over time in relation to the unfinished business in the soul of the work.”[12] As I walk the path of my research I have to come to recognize that the path does not end, I will only choose to stop treading it at a certain moment. As Romanyshyn goes on to say, “there is never simply an ‘after’ of the work, a time when, after the work is finished, it is done.”[13]

In addition to literary and artistic comparative analysis, I will also be doing biographical and historical analysis. I believe that life context is essential to understanding any person’s work, particularly when the material is as intimate as the Red Books are to their authors. Therefore, I will delving into all the available biographies of both Tolkien and Jung, looking for how the external experiences of their lives may have shaped their imaginal explorations. In order to put their life stories into context I will also be looking at the historical landscape in which Jung and Tolkien lived their lives. What cultural, political, ecological, and other pertinent factors were shaping their experiences? How did their imaginal experiences and expressions relate to or differ from their contemporaries? Looking at the larger context in which Jung and Tolkien were each having their imaginal experiences will shed light on the significance of the similarities in their work, whether the correlations are unique to them or are reflective of the culture and historical situation at large.

The final method I will be using to approach this research will be archetypal analysis. There are two ways in which I will be using the archetypal lens: one will be identifying the archetypes present in the stories and symbols expressed by Tolkien and Jung in their works, and the second will be using the empirical data of archetypal astrology to explore the birth charts, world transits, and personal transits relevant to the area of research. The latter archetypal method will illustrate the correlations between the movements of the planets and the manifestations of their archetypal energies in world events as well as in the personal lives of Tolkien and Jung. Thus, this aspect of archetypal analysis will be done alongside the biographical and historical readings of the material. The astrological perspective can shed light on the collective energies manifesting in world events during specific time periods, or on the energies being carried by individuals as reflected in their personal transits and natal charts. For example, the primary years of creative imagination for Jung and Tolkien, beginning in 1913, took place under the opposition of the planets Uranus and Neptune, which archetypally correlates with

widespread spiritual awakenings, the birth of new religious movements, cultural renaissances, the emergence of new philosophical perspectives, rebirths of idealism, sudden shifts in a culture’s cosmological and metaphysical vision, rapid collective changes in psychological understanding and interior sensibility . . . and epochal shifts in a culture’s artistic imagination.[14]

Recognizing that these transits were taking place can bring greater illumination to the imaginal experiences Jung and Tolkien were undergoing during this time.

The same archetypal eye that can recognize the astrological patterns manifesting in both personal and worldly events can also be turned inward to interpret the stories and images expressed in the Red Books. The second form of archetypal analysis will therefore be done in conjunction with the literary and artistic analysis discussed before. An archetypal lens will allow the symbols inherent in the material to speak a common language, allowing correlations to be more discernible.

One final methodological approach I am taking to my dissertation research is the analogical approach used by Daniel Polikoff in his book In the Image of Orpheus: Rilke: A Soul History. This method can be seen as a means of encompassing the five methods I just delineated and unifying them into a multivalent, symbolic lens. The analogical approach allows the researcher to recognize analogies between artistic expression and life event, or between life event and archetype, or between archetype and myth, and so forth. By reading through the many layers present, the meanings of the symbols in the work can continue to reveal themselves indefinitely.

While the empirical orientation of this dissertation is the identification of similarities between Jung’s and Tolkien’s Red Books, the deeper question at work in the research is what the implications are of these correlations. Therefore, not only are the similarities of import, but the differences are as well. If the similarities in their work point toward a common experience of the imaginal realm, what do the differences indicate? As I approach these questions in my research I have to be careful not to impose my own preconceived ideas onto the material, but rather remain open to what is being communicated directly to me by the work. As Romanyshyn writes,

Not so impatient to engage the work in any conscious way, not so quick to irritate the work into meaning, the researcher who uses the alchemical hermeneutic method is content to dream with the text, to linger in reverie in the moment of being questioned, as one might, for example, linger for a while in the mood of a dream.[15]

Here is both the gift and the challenge of an imaginal approach to research, because it can be such a trial to stay with the material when no clear answers seem to be arising, when the meaning or understanding one is searching for is not on the surface. Romanyshyn goes on:

Thus, the alchemical hermeneutic researcher begins with a kind of emptiness. It is an emptiness that has the qualities of patience and hospitality, which leave the researcher continuously open to surprise, an openness that, in having no plans, simply invites the text—the work—to tell its tale.[16]

When I first began my research on the Red Books there were times when I was sure that I would find nothing, no correlations to back up the intuition I had that some relation existed between these works. Yet, as Jung wrote, intuition “is not concerned with the present but is rather a sixth sense for hidden possibilities.”[17] I felt I had to surrender myself to whatever the text wanted to reveal. Romanyshyn speaks of how “The ego as author of the work has to ‘die’ to the work to become the agent in service to those for whom the work is being done.”[18] It may not even be clear for whom the work is being done, but that too is part of the surrender of ego to the soul of the work. “Within an imaginal approach,” Romanyshyn writes, “that larger tale to which one is in service is the unfinished business in the soul of the work, which makes its claims upon a researcher through his or her complexes for the sake of continuing that work.”[19] An essential part of the imaginal approach is recognizing that the work itself has soul, and has agency. The work guides the researcher as much as the researcher guides the work.

Soul means many things to many different people, and its elusive meanings have changed and evolved over millennia as well. From the depth psychological perspective soul, or Psyche, is primary. We exist in Psyche’s realm. “Soul is not inside us,” Romanyshyn writes. “It is on the contrary our circumstance and vocation. It surrounds us, and we are called into the world, as we are called into our work, through this kind of epiphany.”[20] Not only is the researcher ensouled, the researcher’s work is as well. An alchemical hermeneutics acknowledges that embeddedness in soul and seeks to articulate it, to give “voice to the soul of one’s work” by “allowing oneself to be addressed from that void, which depth psychology calls the unconscious.”[21]

How does one listen to the void? How does one open oneself to the unspoken wisdom of the unconscious? In an imaginal approach, this orientation is called a poetics of the research process. Not literally drawing on poetry, it is a means of entering into mythopoetic consciousness. In Romanyshyn’s words: “A poetics of the research process, then, is a way of welcoming and hosting within our work the images of the soul, a way of attending to more than just the ideas or facts, and it requires a different style, a different way of being present.”[22] More specifically, “A poetics of research invites the researcher to become the work through the powers of reverie and imagination and then let go of it.”[23] Traditional hermeneutics does not explicitly give a place to reverie and imagination in its methodological process, yet they are epistemological forces shaping the work nonetheless, although oftentimes unconsciously. A poetics of research allows the knowledge and understanding born from reverie the space to unfold. “In reverie,” says Romanyshyn, “we are in that middle place between waking and dreaming, and, in that landscape, the borders and edges of a work become less rigid and distinct. . . . In reverie, the work takes on a symbolic character and is freed of its literal and factual density.”[24]

Part of my research process has been learning to cultivate these moments of reverie while in direct relationship with Jung’s and Tolkien’s material, particularly while doing the literary and artistic analysis. When reading Jung’s Red Book for the first time, I created a ritual practice around the reading to honor the feeling I had that I was approaching a sacred text. The practice was in some ways communicated to me by the confluence of my embodied reaction to the material and the text itself. At first I would sit down to read with the intention of taking in as much material as possible, as I might with any other text I was researching. But I began to find after about eight pages I would emotionally shut down and disconnect from what was on the page; I was saturated, and literally could absorb no more. I would sit staring at the page wondering what had happened. Romanyshyn speaks of the role the body plays in our research, and that one should pay attention to those moments when we disconnect from the text, when we seem to drift off intellectually and depart from ourselves and what is present before us.[25] Something important is being communicated in that moment, and instead of reprimanding ourselves for “spacing out” we can instead learn to cultivate that place of reverie. One lesson I received from paying attention to this moment of splitting off from the text was that its richness could not be digested if I sought to take in too much at once. Therefore, I created a daily practice of reading eight pages—no more and no less—of The Red Book at a pace where I could absorb more of the material, and also be absorbed into the material. Such an approach, according to Romanyshyn, “deepens research and makes it richer by attending to the images in the ideas, the fantasies in the facts, the dreams in the reasons, the myths in the meanings, the archetypes in the arguments, and the complexes in the concepts.”[26]

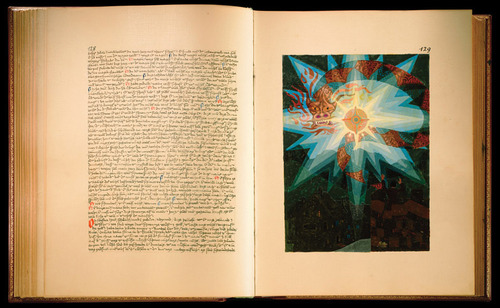

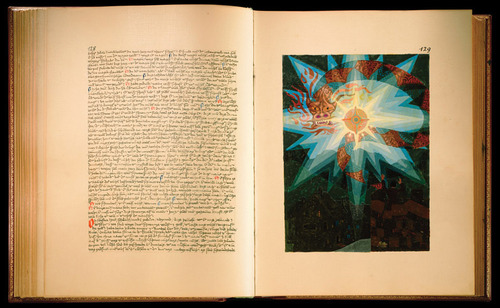

Another aspect of my daily practice with Jung’s Red Book was that I only read from the original text. The Red Book has been published with the same size pages as Jung’s original manuscript, making it a weighty volume fifteen inches in height and eleven inches wide. Jung created The Red Book to look and feel like a medieval manuscript, and when one sits and reads it one cannot help but feel like a monk pouring over an ancient text. One must sit up at a table to read the book because it is too heavy to hold in one’s lap; the turning of each page feels like an accomplishment, giving the sense that the turning of a leaf has its consequences. Although a reader’s edition, as well as digital versions of the text, are available, I had an intuition I would learn more from the volume if I sat with its weight each day and learned from it at the emotional and physical levels, as well as at the intellectual level.

When approaching Tolkien’s work I developed a few different practices to bring the same care and reverence as I was bringing to Jung’s Red Book. I have read much of Tolkien’s oeuvre repeatedly over the course of my life, and to a high degree have internalized much of the content. When I came across a correlation in Jung’s work, it usually triggered my memories of some passage or aspect of Tolkien’s stories that I had read years before. The texts I was consulting of Tolkien’s, in the initial research, were a part of me, imprinted on my memory and soul. In some ways, my own memory could be seen as one of the texts being consulted in the research. Therefore, I decided to try to bring my memory even more consciously into the process. Certain passages I chose to memorize, to internalize the exact wording of Tolkien’s writing. For me this was another way of attending to the poetics of research, to become one with the poetics of the material. Another way in which I sought to bring ritual practice into my reading of Tolkien’s work was reading certain stories out loud with my partner. By presencing the language to each other, hearing the shape of the words—particularly the words of languages that Tolkien invented—gave greater life to the text and allowed the imaginal experience to lift off the page. Both sitting with Jung’s Red Book and reading Tolkien’s stories out loud became practices of trying to recreate their own imaginal experiences, of attempting to come to a greater understanding of their journeys into the realm of the imagination.

From these practices of physically sitting with the weight of the texts, as well as with the artwork created by both men, I realized that another part of the research I wish to undertake is to travel to the homelands of Tolkien and Jung to attempt to find any additional artwork in their archives that have not yet been published. In the Bodleian Library in Oxford, England is an archive of Tolkien’s work that I know contains several pieces of artwork not previously published. I am particularly interested in a series of drawings from his unpublished sketchbook The Book of Ishness, which is a series of imaginal drawings created at the exact same time as the early years of Jung’s Red Book period. While some of the images have been published in Hammond and Scull’s J.R.R. Tolkien: Artist & Illustrator, a footnote in that book lists the titles of the many drawings from the series that remain unpublished. I am curious to see if any of these bear a resemblance to more of Jung’s artwork. Thus I would also want to travel to archives in Zürich, Switzerland where the papers and artwork of Jung are held, to see what other images of his have not been published.

Approaching research from a place of reverie can open unexpected doorways into the research topic. For example, my research question regards the nature of imaginal experience, and one day when I was sitting with The Red Book I closed my eyes after reading a particularly beautiful passage about the sea. As I my eyelids descended, an inner world opened up before me: I had the sense of diving into a still pool in a forest glade and of swimming down, down, down. Long past the moment I felt I should have touched the bottom I was still descending. Then, instead of touching the base of the pool, I found myself surfacing from another body of water. The world had inverted, turned upside down. The waters in which I found myself swimming stretched as far as the eye could see under a grey sky, wan sunlight illuminating the backs of the clouds. As I began to swim forward I saw the white shores of what seemed to be an island. I swam up to the beach and pulled myself from the waters. A forest grew not far from the water’s edge, and I walked through the soft sands on a path under the trees. As I began to ascend the path, the vision started to fade and I reopened my physical eyes to The Red Book lying open before me.

This experience was not looked for in my analyses of Jung and Tolkien, but it gave me an experiential understanding of what active imagination felt like. Imaginal experiences born of reverie or dreams—of sleep or waking—can contribute to the methodological approach to the research. However, as Romanyshyn writes, “dreams as portals into research are not the data of research.”[27] While the content of this vision will not be a part of my dissertation, the experience of it has shaped me and therefore will implicitly shape the nature of the work.

The subject of my dissertation is the descent into soul, the threshold into the world of the imagination that both Jung and Tolkien seemed to have crossed on their life journeys. Part of what I am attempting to understand was their own methodological approach to those journeys. As Romanyshyn writes, “the descent into the depths of soul is easy. Finding our way back, however, is the art and is the work.”[28] The Red Books were Tolkien’s and Jung’s means of finding their way back from the world of soul. By treading the path again and again it becomes easier for others to follow in their footsteps. In creating a methodology I am attempting to find the maps they used on their imaginal journeys, and to survey the terrain in my own right.

Part of the intuition that drew me into this research was a sense of recognition of the experiences both Jung and Tolkien had undergone. At age nine when I first encountered the realm of Middle-Earth by having The Hobbit read aloud to me, I acknowledged that there was something deeply familiar about this territory. The sound of the names, the feeling of the places and the people all seemed to be echoing something I had somehow known before. When, over a decade and a half later, I encountered Jung’s Red Book I had that same sense of familiarity, and again could not place from whence it came. This very feeling Romanyshyn addresses as why we are drawn to do the research that we do, what in the work calls us forth to attend to it. He writes, “Research with soul in mind is re-search, a searching again, for something that has already made its claim upon us, something we have already known, however dimly, but have forgotten.”[29] The process of research is that of anamnesis, the un-forgetting that is the philosopher’s quest, as Plato articulates. The inexplicable affinity and familiarity the work holds for the researcher is the soul of the work calling to the soul of the researcher. It is a call to action within the realm of soul itself. That call ignites the desire to remember, to re-search, to find what we sense is there. As quoted in the epigraph opening this essay, “Maybe all our re-search reenacts the Gnostic dream of the fall of soul into time and its desire to return home.”[30]

Bibliography

Carpenter, Humphrey. J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000.

Hammond, Wayne G. and Christina Scull. J.R.R. Tolkien: Artist & Illustrator. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000.

Hillman, James. Re-Visioning Psychology. New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 1992.

Jung, C.G. Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Edited by Aniela Jaffé. Translated by Richard and Clara Winston. New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1989.

–––––. The Red Book: Liber Novus. Edited by Sonu Shamdasani. Translated by Mark Kyburz, John Peck, and Sonu Shamdasani. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009.

Polikoff, Daniel. In the Image of Orpheus: Rilke: A Soul History. Wilmette, IL: Chiron Publications, 2011.

Romanyshyn, Robert. The Wounded Researcher: Research with Soul in Mind. New Orleans, LA: Spring Journal Books, 2007.

Samuels, Andrew, Bani Shorter and Fred Plant. A Critical Dictionary of Jungian Analysis. New York, NY: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986.

Tarnas, Richard. Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View. New York, NY: Viking Penguin, 2006.

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Edited by Humphrey Carpenter, with Christopher Tolkien. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000.

–––––. The Lord of the Rings. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1994.

–––––. “On Fairy-Stories.” In The Monsters and the Critics. Edited by Christopher Tolkien. London, England: HarperCollins Publishers, 2006.

–––––. The Silmarillion. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2001.

–––––. “Smith of Wootton Major.” In Tales from the Perilous Realm. London, England: HarperCollinsPublishers, 2002.

[1] Robert Romanyshyn. The Wounded Researcher: Research with Soul in Mind (New Orleans, LA: Spring Journal Books, 2007), 268.

[2] Romanyshyn. The Wounded Researcher, 9.

[3] Ibid, 259.

[4] Romanyshyn. The Wounded Researcher, 215.

[5] Ibid, 273.

[6] Ibid, 270.

[7] Romanyshyn. The Wounded Researcher, 221.

[8] Ibid, 4.

[9] Ibid, 222.

[10] Romanyshyn. The Wounded Researcher, 235.

[11] Romanyshyn. The Wounded Researcher, 225.

[12] Romanyshyn. The Wounded Researcher, 233.

[13] Ibid, 262.

[14] Richard Tarnas, Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View (New York, NY: Viking Penguin, 2006), 356.

[15] Romanyshyn. The Wounded Researcher, 223.

[16] Ibid, 224.

[17] C.G. Jung, qtd. in Romanyshyn. The Wounded Researcher, 291.

[18] Romanyshyn. The Wounded Researcher, 6.

[19] Romanyshyn. The Wounded Researcher, 83.

[20] Ibid, 9.

[21] Ibid, 15.

[22] Ibid, 12.

[23] Romanyshyn. The Wounded Researcher, 11-12.

[24] Ibid, 87.

[25] Ibid, 296-7.

[26] Romanyshyn. The Wounded Researcher, 12.

[27] Romanyshyn. The Wounded Researcher, 98.

[28] Ibid, 15.

[29] Romanyshyn. The Wounded Researcher, 4.

[30] Ibid, 268.

The Chronicles of Narnia tell the full arc of the history of that realm, from its creation in The Magician’s Nephew and its parallels with Genesis, to The Last Battle, with its coming of the Antichrist and the Last Judgment, ending in the extinguishing of the world of Narnia. Yet each one also feels somewhat disparate from the others, in tone, style, and feeling. They almost seem to not quite hang together, while at the same time being compelling and hugely popular. My two favorite stories were The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe and the Dawn Treader, interestingly perhaps the most and the least allegorical of the tales respectively. Although The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe tells of the Crucifixion and the Resurrection, with Aslan the Lion representing Christ, that story also feels like the one in which the pure realm of Narnia, apart from any allegorical meaning, shines through most brightly. The world of Narnia has a life of its own in that tale, more exuberant than in any of the other stories, perhaps in part stemming from the fact it was the first book Lewis wrote in the series. The four Pevensie children, the frozen Lantern Waste, Mr. Tumnus the Faun, Aslan himself, all have an imaginal reality to them which stands above and beyond the allegory that later came to be told through their actions. The Christian allegories Lewis is telling are taking place in a genuine part of Faërie, to draw on Tolkien’s term for the Imaginal Realm. Indeed, these aspects of Narnia came to Lewis before the Christian themes worked themselves into the tales, and Aslan himself seemed to be appearing in Lewis’s dreams for some time before he began writing, as the Imaginal Realm can so often do when the veils between worlds begin to thin.

The Chronicles of Narnia tell the full arc of the history of that realm, from its creation in The Magician’s Nephew and its parallels with Genesis, to The Last Battle, with its coming of the Antichrist and the Last Judgment, ending in the extinguishing of the world of Narnia. Yet each one also feels somewhat disparate from the others, in tone, style, and feeling. They almost seem to not quite hang together, while at the same time being compelling and hugely popular. My two favorite stories were The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe and the Dawn Treader, interestingly perhaps the most and the least allegorical of the tales respectively. Although The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe tells of the Crucifixion and the Resurrection, with Aslan the Lion representing Christ, that story also feels like the one in which the pure realm of Narnia, apart from any allegorical meaning, shines through most brightly. The world of Narnia has a life of its own in that tale, more exuberant than in any of the other stories, perhaps in part stemming from the fact it was the first book Lewis wrote in the series. The four Pevensie children, the frozen Lantern Waste, Mr. Tumnus the Faun, Aslan himself, all have an imaginal reality to them which stands above and beyond the allegory that later came to be told through their actions. The Christian allegories Lewis is telling are taking place in a genuine part of Faërie, to draw on Tolkien’s term for the Imaginal Realm. Indeed, these aspects of Narnia came to Lewis before the Christian themes worked themselves into the tales, and Aslan himself seemed to be appearing in Lewis’s dreams for some time before he began writing, as the Imaginal Realm can so often do when the veils between worlds begin to thin.